The European Court of Justice (CJEU) has issued some further decisions related to data protection law and surveillance since I wrote about this subject two weeks ago.

These decisions, along with the increasingly urgent need to settle the question of UK-EU data flows in any trade agreement, have prompted me to try and paint a picture of where things may be going.

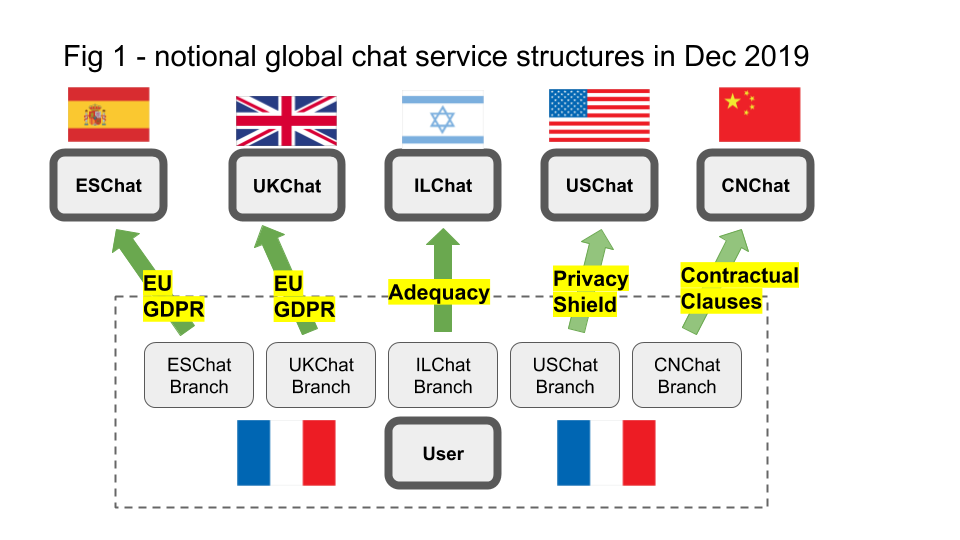

For this exercise, I will consider the situation of some notional internet chat services based outside of the EU, along with one control example from an EU country, being offered to users in France.

[NB this is only one part of the picture but plenty to chew on in this post, and I will look at the related issues for services with an EU HQ working with non-EU subsidiaries and partners separately].

Each of my notional companies – ESChat, UKChat, ILChat, USChat and CNChat – has set up a local subsidiary in France but has all of their actual data processing infrastructure in the country where they have their company HQ – Spain, the UK, Israel, the US, and China respectively.

They have each established a legal structure in which the French subsidiary is considered to be collecting and deciding how to use the data of French users, while the HQ company provides back-end services at their direction.

In legalese, the local subsidiary is the ‘data controller’ while the HQ company is a ‘data processor’ working on its behalf.

Importantly, this means that the subsidiary is considered to be engaged in data transfers from the EU to an entity outside the EU (except for ESChat), even if they are both part of the same business.

From a technical point of view, the data from individual users anywhere in the world actually travels directly to and from the servers in each HQ country, but from a legal point of view the local subsidiary is deemed to sit in the middle.

We can look first at how the legal structures as we understood them in December 2019 might have worked for companies like these.

If these imaginary services were setting up their operations in December 2019, they would all have been able to find mechanisms that provided legal cover for their transfers of French user data to their HQ countries.

ESChat and UKChat have the most robust permissions for the data flows as Spain and the UK are both (at this date) fully within the EU’s GDPR framework which assumes that all intra-EU transfers meet the required standards.

ILChat has the next most robust mechanism as it is able to use an ‘Adequacy’ decision where the European Commission has recognised the State of Israel as offering equivalent privacy protections to those of the EU.

USChat also benefits from a special EU-US arrangement called the Privacy Shield that is not as comprehensive as an adequacy decision but is still intended to offer a relatively simple method to legitimise flows.

The Chinese service cannot look to any special arrangement with the EU, but might use standard legal language in the contracts between the subsidiary and HQ as this is considered to be an appropriate legal basis for data transfers from the EU to many other countries.

So at the back end of 2019, while concerns had been raised about a number of these arrangements, all of our services might feel they had some kind of legal footing for transferring data between the different parts of their business.

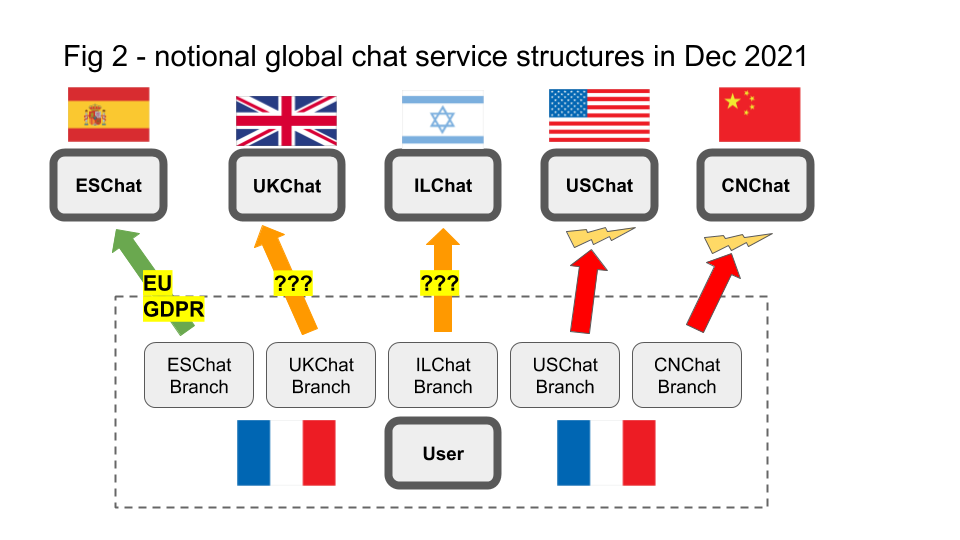

To illustrate the significance of the change that appears to be underway, we can now fast forward to how things may look in December 2021 if the direction of travel continues as it has done during 2020.

First, the good news, for ESChat it is business as usual!

There is no reason to expect there to be any change to the free flow of data between EU member states, though it is not impossible that intra-EU flows could be challenged if an EU country introduced national laws that were in breach of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The UK will go into 2021 with a domestic implementation of the GDPR and believing that its law is consistent with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights to which it was a signatory until very recently.

It might them seem a no-brainer for the UK to be granted Adequacy status as part of its ongoing deal with the EU and for this to be robust and defensible for as long as it makes no significant changes to its privacy or surveillance laws.

But there is a significant chorus of voices from privacy experts who believe that any such EU-UK Adequacy decision could (and should) be challenged and that there would be a strong case for the CJEU to invalidate it.

I will dig more into the ins and outs of why this might be the case when I go on to look at how we have got here, but for now there are grounds to place a question mark over whether UKChat would be able to transfer data from France to the UK in December 2021.

The story for ILChat is similar to that for the UK though from a more divergent starting point with Israel not having been a member of the EU.

The State of Israel has solid ‘EU-like’ data protection legislation and an independent regulator but it also has strong national security agencies and is considered a leader in surveillance technologies and methods.

Commentators looking at the decision on the EU-US Privacy Shield have suggested that the EU-Israel Adequacy decision might be vulnerable on the same basis, ie it provides insufficient protections against state surveillance.

The situation for USChat seems even more precarious given the explicit directions given in the CJEU decision to strike down the Privacy Shield.

The Court has pointed to specific areas where it would expect to see reforms to US national security law before it would find any successor agreement to the Privacy Shield acceptable.

I talked previously about how challenging it is for any country to change its law in such a sensitive area under external pressure, and how there needs to be some kind of transatlantic digital forum to advance this at all.

These talks may happen and could lead to a new EU-US agreement but, until we see signs of progress, USChat will have to work on the basis that most of the options it had for transferring data to the US will be lost.

Turning finally to CNChat, it is notable that the attention of EU cases to date has largely been on transfers to the US reflecting the high levels of usage by EU residents of services with their HQs in the US.

As services originating from China become more popular, with TikTok the current poster child, we can expect more attention to land on EU-China transfers.

If we look at how the CJEU considers the US surveillance regime to be deficient in terms of EU standards, it seems clear that Chinese state surveillance practices are nowhere near to compliance.

Unless it can provide guarantees about the security of data in China to back up its use of standard contractual clauses, which seems unlikely, CNChat is going to need to find new mechanisms or restructure.

Why This Shift?

The dominant concern in this recent debate around whether countries are ‘safe’ for EU data transfers relates to the data collection practices of security agencies.

A right to privacy is seen as compatible with some forms of state surveillance where these can be shown to be necessary and proportionate and authorised in law (per Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights).

But where states scoop up masses of data from people who are not themselves suspected of anything, then the presumption is that this likely contravenes the principles of necessity and proportionality, even where it is authorised in law.

The CJEU has considered this on a number of occasions and took the bold step of striking down a Directive that created a regime for the retention of bulk communications data across the EU.

It returned to this subject with judgements on October 6th that both answer one of the criticisms of their past decisions about EU-US data transfers, and open up an interesting angle on future agreements.

The criticism is that the EU effectively gives its Member States a ‘free pass’ in that their national security laws are exempted from consideration by the CJEU by virtue of the EU Treaties.

The recent judgement takes a significant step in extending EU law into the area of data collection for national security purposes that a number of member states argued should be solely a national competence.

In essence, it says that while national security is indeed the sole preserve of national governments, Member States cannot pass laws that would require companies to break EU law, in this case the specific piece of EU privacy law that covers the privacy of electronic communications.

This is expressed succinctly and directly in the headline from their press release :-

The Court of Justice confirms that EU law precludes national legislation requiring a provider of electronic communications services to carry out the general and indiscriminate transmission or retention of traffic data and location data for the purpose of combating crime in general or of safeguarding national security

CJEU Press Release No 123/20

On the face of it this ‘levels the playing field’ with the CJEU saying the collection of bulk communications data is unacceptable whether done by an EU Member State or the US (or potentially the UK or Israel in the context of their Adequacy decisions).

But this statement is followed by a huge ‘however’ that moves towards creating a new standard for bulk data collection that is neither a blanket ban nor a free-for-all and is worth quoting in full :-

However, in situations where a Member State is facing a serious threat to national security that proves to be genuine and present or foreseeable, that Member State may derogate from the obligation to ensure the confidentiality of data relating to electronic communications by requiring, by way of legislative measures, the general and indiscriminate retention of that data for a period that is limited in time to what is strictly necessary, but which may be extended if the threat persists. As regards combating serious crime and preventing serious threats to public security, a Member State may also provide for the targeted retention of that data as well as its expedited retention. Such an interference with fundamental rights must be accompanied by effective safeguards and be reviewed by a court or by an independent administrative authority. Likewise, it is open to a Member State to carry out a general and indiscriminate retention of IP addresses assigned to the source of a communication where the retention period is limited to what is strictly necessary, or even to carry out a general and indiscriminate retention of data relating to the civil identity of users of means of electronic communication, and in the latter case the retention is not subject to a specific time limit

CJEU Press Release No 123/20 (my emphasis)

Having said that Member States cannot routinely require the collection of bulk communications data, the CJEU then describes a two part test for when there can be an exception to this rule :-

- A Member State must be “facing a serious threat to national security that proves to be genuine and present or foreseeable”; and

- “the decision imposing such an order, for a period that is limited in time to what is strictly necessary must be subject to effective review either by a court or by an independent administrative body whose decision is binding, in order to verify that one of those situations exists and that the conditions and safeguards laid down are observed.”

This is a helpful new insight into what the CJEU might consider to be the characteristics for acceptable bulk data collection.

If we look at my notional chat services, it seems likely that the Spanish government would be able to meet these conditions if it was minded to ask ESChat for comprehensive communications data including on its French users.

Spain can, sadly, point to recent terrorist attacks from a variety of different factions as evidence that it faces real and ongoing national security threats.

As long as it produced convincing evidence to an appropriate court then it would be able to secure a time-limited (but renewable as long as the threat remained) order for the collection of bulk communications data.

This decision also provides interesting input for any discussions about certification of the UK, Israel and the US as safe countries for data flows.

While this would not answer all of the open questions, common standards for permitting bulk data collection would help address one of the major issues that has come up.

It seems incontrovertible to say that the UK, Israel and the US each face serious ongoing national security threats so they would meet the first test that has been set for EU Member States.

They would need to look at whether and how they can demonstrate that their orders are sufficiently time limited and that they are subject to review before an appropriate court or administrative body to meet the second test.

But if the debate is about whether they are meeting the same standards as EU Member States for the use of bulk data collection then there may be more common ground than if it is predicated on there being no way for non-EU countries to use this tool under any circumstances.

A ‘No Transfers’ Model

As a final thought exercise for this post, we can consider the choices that a new entrant into this market might make based on their assessment of the ongoing legal situation.

We can imagine a new service, USChat2.0, which started out wholly in the US but is now considering its options for expansion into the EU market.

One of the features of the GDPR is that it requires businesses anywhere in the world to apply GDPR protections to the data of EU users if they are actively targeting their services at people in the EU.

This does not necessarily mean every business has to create a subsidiary in the EU, but they do have to accept the legal obligation to treat EU data according to the terms set out in the GDPR, and appoint someone to represent them with EU data protection regulators.

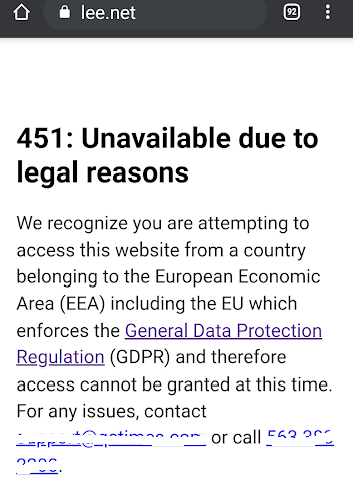

Businesses with little interest in EU users may decide it is not worth the hassle and so instead make it clear that they are not targeting EU users.

We saw a number of US news websites take this approach when the GDPR initially came into force and, while more publishers have since decided they can handle EU user data, others are still deterring visits from people whose IP address appears to be in the EU.

But in our case, USChat2.0 actively wants to expand into the EU so is prepared to set up systems to handle EU data in accordance with the GDPR.

One commitment it cannot make is that it will refuse to comply with any orders from US authorities to disclose data where these are correctly served and enforceable,

USChat2.0 could make this clear to EU users when they sign up, telling them that it will indeed apply GDPR standards to their data, but that it is also subject to US law and providing links to information about US surveillance practices.

The question may then be raised as to whether USChat2.0 is actually complying with the GDPR if it has to make this reservation for access by the US authorities?

This reservation would not be allowed for an entity in the EU that was transferring data to the US, as the recent court decisions make clear, so ‘GDPR compliance’ has a different meaning depending on the company structure.

There is a legal logic to court decisions saying that an entity within the EU must respect EU data protection rights in all respects at all times, including securing appropriate guarantees around any data it sends outside of the EU.

There is equally a logic to recognising that non-EU entities have to respect any legal obligations in their jurisdictions, and so can only apply EU data protection rights to the extent that these do not conflict with their domestic obligations.

If this distinction is recognised then USChat2.0 could continue to offer its service to people in the EU, but if it is not then they will be placed in the impossible position of having to decide whether to breach EU law or US law.

While the focus is on data transfers today, we may see cases argued about what ‘GDPR compliance’ means for non-EU entities tomorrow, especially if one of the unintended consequences of the debate over transfers is to encourage services to prefer ‘transfer free’ structures.

Ian Brown has (very much with tongue-in-cheek) suggested that global services could reconstitute themselves as EU companies serving the world from the EU as one way of being certain they will avoid all future data transfer problems (at least under GDPR).

Assuming we are not going to see all the world’s companies who collect data from people in the EU move their legal and operational HQs to the EU, we are in for a time of more uncertainty as the meaning of the GDPR is contested and clarified.

A recent paper in the American Journal of International Law nicely summarises how these issues are playing into international trade discussions which is where they may ultimately have to be resolved.

The final sentence of this paper describes how the dynamics of international trade negotiations will be shaped by whether the EU and US diverge or converge on data flows.

The EU and United States commitments to their own mutually inconsistent approaches to regulating cross-border data flows could prove counterproductive in this multilateral setting. Conversely, the ability to agree on a common position could allow the EU and the United States to counterbalance the negotiating power of less democratic states such as China.

Yakovleva, S., & Irion, K. (2020). Toward Compatibility of the EU Trade Policy with the General Data Protection Regulation. AJIL Unbound, 114, 10-14. doi:10.1017/aju.2019.81

The stakes are high for both transatlantic trade and for how the EU and US will approach global standards for data flows.

Sitting in the UK today, there is a heated debate about future standards for food products between the EU, US and UK and how these may impact trade.

Food standards are of course important but it is curious that there seems to be less urgency about agreeing international standards for the economically much larger digital sector.

This may reflect the fact that many of the food issues are more immediately intelligible – we can quickly form opinions on the treatment of farm animals and meat products for example.

If this post does anything (other than annoy people who I readily acknowledge are more expert than I am in privacy law) I hope it will help add to the sense that this is an urgent policy issue which should be high on the political agenda.