There is a lot of discussion at the moment about where and how online services store the data of users from different countries.

A common thread is concern that the governments of countries where online services have their headquarters may use their legal powers to access the personal data of people who live in other countries.

A less ‘user-friendly’ concern, but one which exercises many governments, is frustration that they cannot access the data of their own citizens when they are using an app based in another country,

We see this playing out in the US Government’s efforts to change the ownership model for TikTok, and in a series of court cases in the European Union that have centred on Facebook but have wider implications.

Outside the US and EU, the Government of India has prohibited the use of Chinese apps, Russia has banned some services for not storing their data in Russia, and Turkey is bringing in a new law with data localisation provisions.

In this post, I will describe the challenges that are driving some of these moves and look at how they may play out.

Law Enforcement Access Context

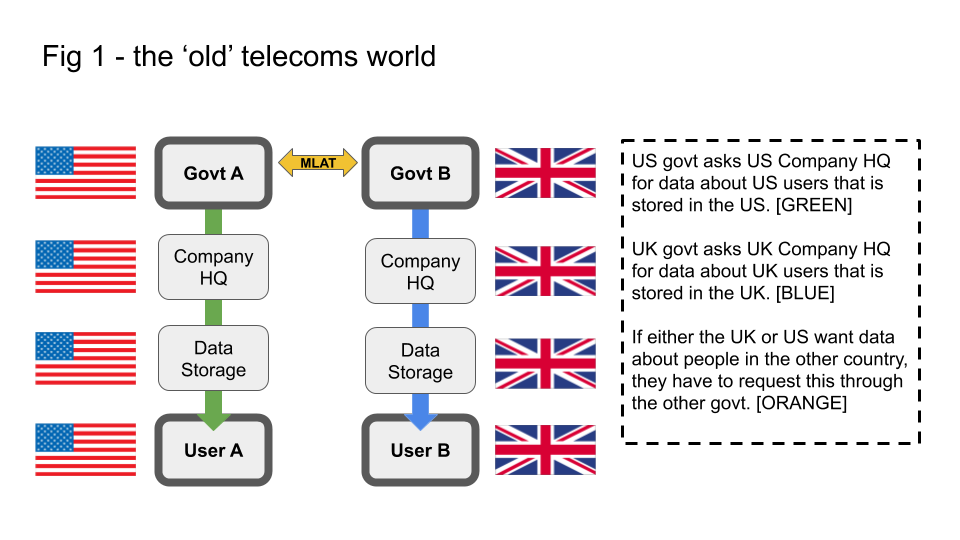

I have created a set of images to illustrate the ways in which different governments might gain access to data.

I have not tried to separate out all the different legal powers and variations between types of agencies – this is rather a simplified model for all types of security-related access to data.

As a baseline, we can look first at the ‘traditional’ model where governments seek data from local telephone (and now internet) service providers.

If the UK government wants data from a local communications company like BT, it is simple for it to do this by compelling this UK company to provide the data using the clear authority it has to do so under UK law.

Similarly, there is a straightforward process for the US government to request data from local US companies like AT&T.

If the US government wants data from a UK service provider like BT, as this is relevant for investigating a crime in the US, it has no power to demand this directly but has instead to make its request via the UK authorities.

The same applies in reverse with the UK authorities having to ask the US government for data held by AT&T that is relevant to a UK investigation.

A standard way to make these intergovernmental requests is via something called a ‘Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty’ or MLAT.

The authorities in each country may also be willing to provide data to each other directly where there are ‘intelligence sharing’ arrangements in place, as there are between the US and UK.

Governments may also seek direct access to data held by companies in other countries by hacking or bribing their way into their systems, but this would be outside of any legal framework agreed between the countries.

This model remains a key part of investigations as the real identity of a suspect often depends on being able to tie their internet (IP) address to their physical address which can usually only be done by local telecoms companies.

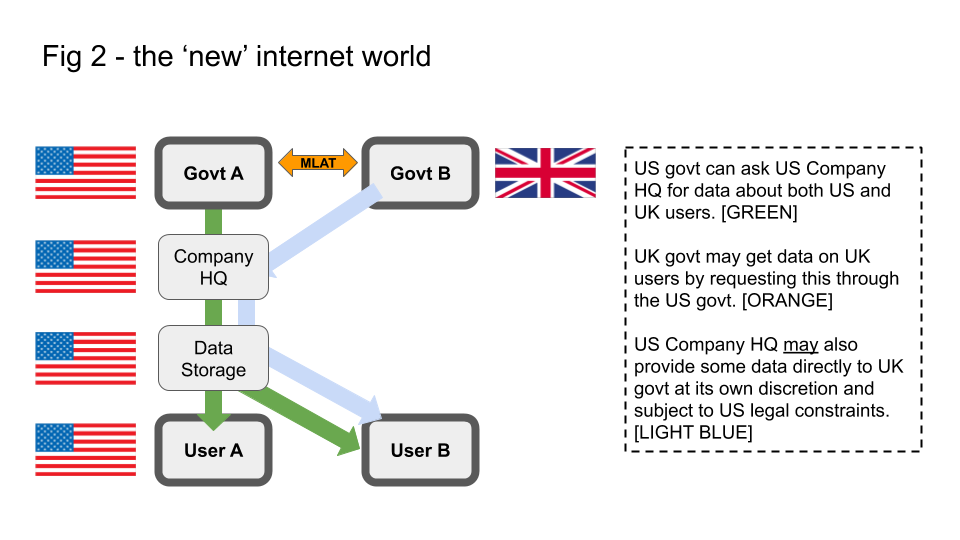

Further upstream, investigators often seek information from the providers of services that run over the internet, such as email, messaging and social media.

Where these services are entirely local to a particular country, then this old model may continue to apply, but we also commonly see people using services offered by companies based in other countries.

This brings us to our second model for governments seeking access to data held by companies that are based outside of their jurisdiction.

We see here that the UK government is no longer able simply to compel a UK company to disclose data about a UK user but needs to request it, in this example, from a company with its HQ in the US.

The US government retains its full powers to compel disclosure of any data held by this company including that relating to people in the UK.

The UK government can again use inter-governmental mechanisms to request the data but may feel these are too slow and cumbersome for routine investigations.

This may not have been a serious problem for the occasional request for data from a US telecoms company that mostly serves US clients, but it becomes a much bigger deal with an internet service that has millions of UK users.

Some internet services insist that all requests go through the full inter-governmental process as a matter of principle, and some civil society groups also strongly support this ‘minimal legal compliance’ model.

More commonly, internet services will start to accept some types of direct request from some governments as they grow their user base.

The US company in this example would want to be confident that when it responds to such a request this does not conflict with human rights standards or result in it breaching US law.

From the perspective of the authorities in a country like the UK, they may be pleased that they can get some data, especially in threat to life cases, but frustrated that they have less access than their US counterparts to data about people in the UK.

This model of a service being offered by a company that is entirely within a single jurisdiction tends to become more complex over time as companies establish subsidiaries and use data centres in other locations.

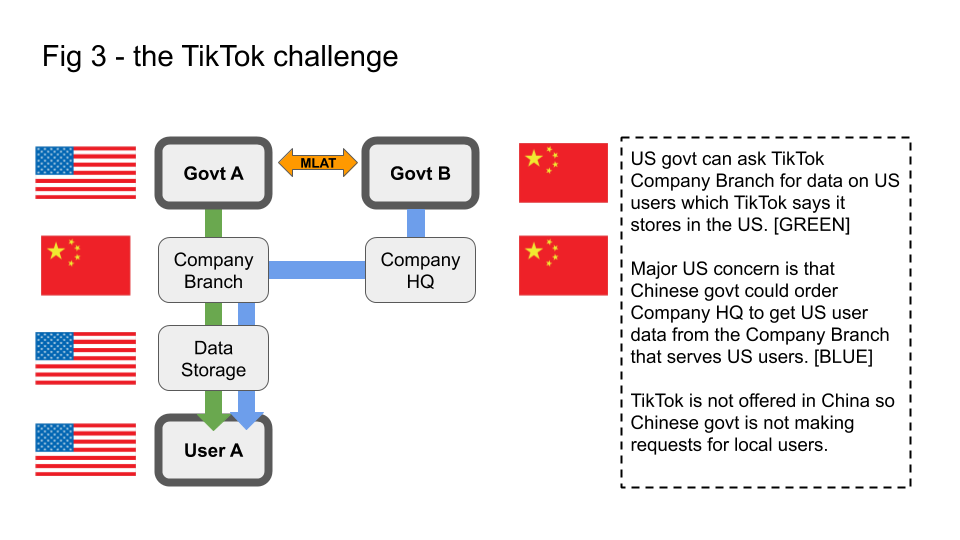

The situations of TikTok and Facebook that are currently under scrutiny reflect these more complex structures of the large successful service.

Turning, first to TikTok, its structure introduces a subsidiary into the mix.

The ultimate owner of the TikTok service is a Chinese company called Bytedance that is fully subject to Chinese law.

The concern expressed by some US policy makers is that this Chinese Company HQ might be compelled under Chinese law to provide data about US users of the service, and that it might seek to comply by ordering its TikTok subsidiary to hand over data.

TikTok has sought to defend itself against this claim by pointing out that it does not store US data in China, and saying that it has never provided data to the Chinese authorities.

Given the secrecy in all countries around national security requests, it is impossible to verify that this is true, and so the US government is seeking to restructure TikTok to block any legal path from the Chinese government to US user data.

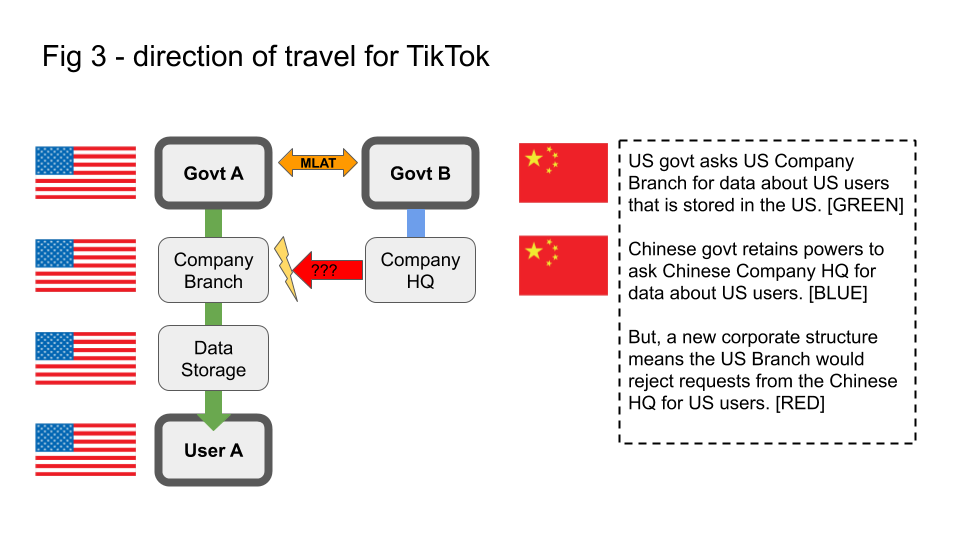

The ownership structure of the subsidiary company that offers TikTok to US users has been identified as the critical area where change needs to happen.

The aim of the US government is to have the service provided to US users by an entity that is within the US jurisdiction and cannot be compelled to provide data to the Chinese government.

There is ongoing debate about the precise structures that would achieve this goal and whether this can happen if the US entity continues to have any kind of ownership relationship with the Chinese parent company.

The intent is clear – the US government has to be confident that the US entity could legally and technically refuse to comply with any request for access to US user data made to Bytedance by the Chinese government.

There are parallels here with the situation we are about to look at in respect of Facebook in the EU.

While the regimes are very different, the concerns of EU courts about potential US government access to EU data echo the US government’s concerns about potential Chinese government access to US data.

We can turn to those EU concerns now with Facebook as an example but noting that the same issues are relevant for many other companies that transfer the data of EU residents to the US.

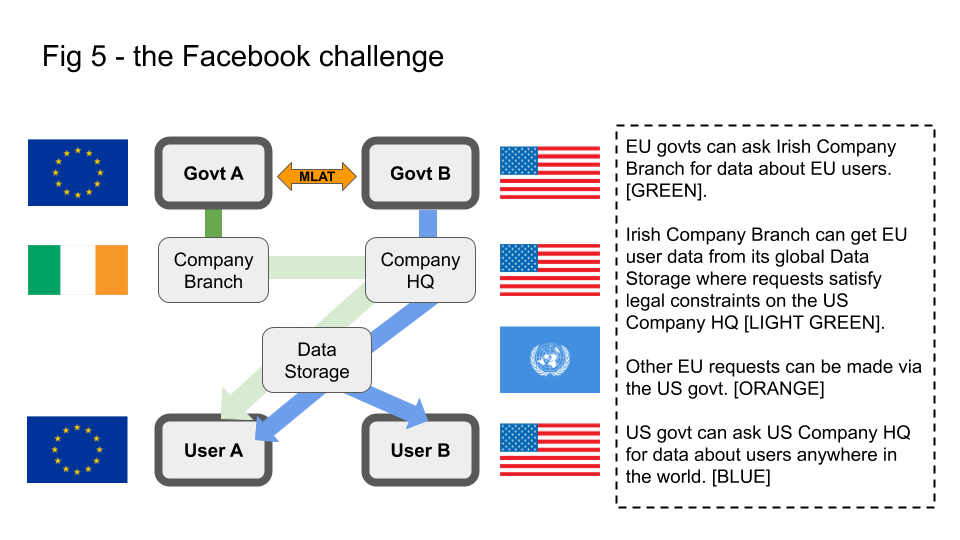

The structure of major services like Facebook differs from the simple model in Figure 2 in that they have large subsidiaries, in Facebook’s case in Ireland, and they store the data of all of their users across a global network of data centres.

The Irish Company Branch provides an entity within an EU jurisdiction where EU governments can send their requests for data.

But the fact that the Irish Company Branch is set up to use its US parent company to process data across the global data centre network, means that it still has to consider US legal constraints when handling these requests.

This remains legally similar to the discretionary disclosure model in Fig 2 and may continue to cause frustration amongst EU security agencies that they feel it is too hard for them to get access to the data of people in the EU.

As with the model in Fig 2, they can address this by using the intergovernmental arrangements, through data sharing with their US counterparts, or by seeking unauthorised direct access to US company systems.

While EU security agencies are frustrated at their lack of power to get data, EU privacy authorities and activists are concerned that the US government has excessive powers to access EU data under the US legal code.

The debate is largely framed in similar terms to the TikTok debate, ie that changes are needed to prevent access by a foreign government, in this case the US.

But we should recognise that there is also a significant lobby within EU governments interested in any changes that would lead to easier access to EU user data that is under the control of US internet services.

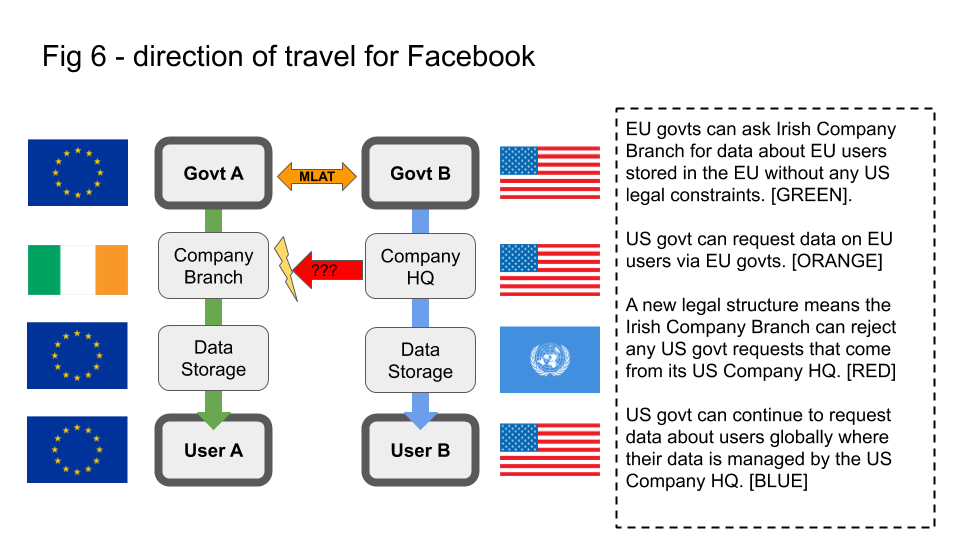

This is still very much a live legal process and it is not clear where this will end up but one possible outcome is that the EU courts force US services to create entities for handling EU data that are insulated from US government requests.

There are two changes from the status quo that may be required to move to a position where the EU data is fully outside of the reach of the US authorities.

First, EU user data would no longer be stored on a global infrastructure that is operated by the US Company HQ.

Companies like Facebook have data centres within the EU already that store slices of the company’s global database, but they do not attempt to segment the data of users from different countries into different datacentres.

There is a lot of technical detail behind why companies choose particular architectures for their infrastructure that is beyond the scope of this post.

In simple terms, having to keep segments of data in specific locations can mean more equipment redundancy, which has a cash cost, and less operational flexibility, which has speed and resilience costs.

There may be little sympathy for internet companies if their costs go up, but it should also not be surprising that the people who design infrastructure for global services are reluctant to implement solutions that they believe are sub-optimal from a technical point of view.

Second, the EU entity would have to be legally able to reject any requests made by the US authorities to its parent company.

As with the TikTok situation, creating such a ‘fully insulated’ subsidiary is legally complex and there has been significant litigation on the subject of when a US company must disclose data held by its non-US subsidiaries.

This litigation led to the CLOUD Act which makes it clear that US authorities can request non-US data held by US companies in other countries but gives companies the right not to comply if this would mean breaking another country’s privacy law.

Where a US company has its EU data solely under the control an EU subsidiary, it would have a case to refuse disclosure to US authorities if this is inconsistent with EU privacy law but may face US legal challenges to this position. .

If the outcomes of these pressures on both TikTok and Facebook are similar – local data storage and a local entity insulated from government demands on the parent company – the political contexts are quite different.

Compare and Contrast

The US moves against TikTok (as well as recent decisions by the Government of India) are overtly political and targeted.

In this scenario, a government sees another country as hostile and is taking steps to reduce the risk that the data of its citizens will get into the hands of the other country’s government via locally headquartered services.

This is part of a deliberate government effort to protect a country against what it sees as a strategic enemy with hostile intent.

We might see Russian data localisation requirements, which have US services in their sights, in a similar light as they are motivated by strategic economic and security concerns.

The EU process by contrast is largely happening outside of the political realm and there is less clarity about what EU policy makers want.

Some people in the EU do think of the US as a hostile force, and their convictions may have been strengthened by the Snowden revelations, and by positions taken by the current US President.

But this seems to be a minority position, while the majority of EU policy makers continue to see the US as a strategic ally over the long-term, even if they have concerns about some aspects of US policy.

Many EU security agencies have good working relationships with their US counterparts and are engaged in operations against common enemies – a stark contrast with the US-China and Russia-US situations.

This majority view of the US as a partner and ally motivated the EU to create mechanisms in EU data protection law that would allow the European Commission to regulate for easy data flows between the EU and US.

But if there was political will to create these mechanisms – known as the Safe Harbour and Privacy Shield – there was also political support for privacy principles that would conflict with them and lead judges to rule them invalid.

There are politicians who are happy with this outcome as they want EU law to prevent the transfer of data of EU citizens to any country where they believe the privacy laws are too weak, and they include the US in this category.

But it is not clear that this is the settled view of all of the EU’s political leadership who may not have been intent on frustrating EU-US commerce when they signed off on the GDPR.

Where Next TikTok?

The situation for TikTok seems resolvable in that a new corporate structure can be created which creates a legal firewall between the entity with access to the data of US users and the Chinese parent company.

This will require some manoeuvring but is helped by the fact that TikTok is not offered to users in China, making it easier for the new entity to be legally prohibited from responding to any Chinese government data requests.

If the US government concerns remain confined to access to data then we may see the ‘TikTok problem’ resolved in this way, but there might be a long tail of additional issues.

There has also been interest in the question of feed algorithms and how these shape the media environment, and these will not be resolved by a new corporate structure for data.

Any attempt to bring the inner workings of the TikTok platform under ‘US control’ may provoke more resistance than doing this for US user data.

We have also seen the new structure for TikTok being talked about as creating a ‘TikTok Global’, though it is unclear whether the intention is for this to be truly global or ‘World Series’ global, ie North American only.

If the plan is to make the US the primary jurisdiction for all TikTok users around the world, then this would open up a new front with countries, like those in the EU, that have concerns about US law.

This would pull TikTok into the debate about US-EU data flows that I will try to project forward now.

Where Next EU-US?

The most passive position the EU could take is for it to say that it sees this as entirely a judicial matter – it has done its job with the GDPR and it is now up to the Courts to interpret it.

But this seems unsustainable given that continued moves to restrict transatlantic data flows will have an impact on both trade and security matters and these are highly political arenas.

It seems much more likely that, sooner or later, the EU is going to have to make a fresh political decision about transfers of data from the EU to the US.

In doing so, it could decide that US access to EU data is a strategic threat and that it would positively wish for EU law to make this as difficult as possible.

This would be similar to the US approach to China where there is a clear political will to disrupt data transfers.

This does not appear to be the majority EU position today, but views might shift further in that direction if the US seems uninterested in privacy rights or to have no regard for the interests of any country other than the US.

Assuming the majority view remains that the US is a strategic ally, and that the EU would like to enable rather than frustrate transatlantic data transfers, then there will be a need to sit down for bilateral negotiations.

The EU’s starting position would be to seek changes in US law sufficient to give the European Court of Justice confidence that the US is a safe country for storing EU data under the terms of the GDPR.

This would mean asking for changes in very sensitive areas of national security legislation and we should not underestimate how challenging this would be in the context of any bilateral agreement.

We see a taste of this in the UK Brexit debate where there are suggestions that the US might try and force changes in UK regulation to accommodate its products and services as a condition of a new trade agreement.

The reaction from UK politicians and public is understandably hostile to the idea that they could be ‘bullied’ into changing their laws to suit another country.

With national security issues, the stakes are raised even higher so there will be significant barriers to a solution that is based solely on the US ‘just needing to change its surveillance laws’.

We might see the US willing to grant some new special protections to EU data under the control of US companies if they were confident that this would resolve the matter over the long-term.

For this to be the case, there may need also to be some changes on the EU side to reduce the likelihood that this continues to be repeatedly litigated.

It is notable that there are already significant carve-outs from the GDPR for the national security interests of EU member states, but these are not applied to the activities of other governments.

The activities of EU security services are explicitly excluded from its scope in Article 2 of the GDPR –

This Regulation does not apply to the processing of personal data:

1. in the course of an activity which falls outside the scope of Union law;

2. by the Member States when carrying out activities which fall within the scope of Chapter 2 of Title V of the TEU;

3. by a natural person in the course of a purely personal or household activity;

4. by competent authorities for the purposes of the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties, including the safeguarding against and the prevention of threats to public security.

General Data Protection Regulation, Article 2

If the GDPR is not directly applicable in respect of access to EU user data by EU security agencies, as is sometimes incorrectly assumed, there are other instruments that are relevant.

There is a separate EU legal framework for data protection in the context of regular law enforcement (not national security) activities that is tailored to the needs of law enforcement agencies,

There may also be provisions in national law that clarify how data protection rights have been restricted for public interest purposes under the terms of Article 23 of GDPR.

For national security activities, there is a reliance on the fact that EU Member States are all signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights and the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights as a constraining force.

These are useful instruments that have each been relevant for important decisions affecting surveillance law.

Citizens can challenge EU governments in the European Court of Human Rights alleging infringement of their Article 8 privacy rights and countries have made changes to their laws in response to judgements.

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights has been cited in a number of privacy cases and was an important element in the 2014 decision to strike down the EU’s Data Retention Directive.

One option for the EU might consider is a similar carve-out to the one it offers for EU security activities for some national security activities of other governments, like the US, that it has deemed to be friendly.

A carve-out of this kind could itself be challenged as incompatible with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, but any resulting case would require a direct comparison between the surveillance practices of EU Member States and those of the US government.

A consideration of the reality of EU government surveillance, as enabled by national law rather than EU-wide legal instruments, may demonstrate more equivalence in practice than has some times been assumed.

Hard Choices

There is no easy option in the EU-US relationship for the policy maker who is interested in both privacy and economic interests.

The US-China situation is much simpler in that the economic and privacy goals are aligned – “hey, we can both protect our citizens’ data and hurt our economic competitors, what’s not to like!”

For the privacy purist, the option of changing EU law will be unthinkable and the only right path is to double down on making data flows difficult until the US sees sense and reforms its surveillance laws.

At the other end of the spectrum, there will be those who have never been overly concerned about surveillance either at home, or in the US which they see as an ally.

These policy makers may see the solution in simply creating new carve-outs for the US, and, while it seems unlikely that this would be a majority view in the EU today, it may be the path that the UK decides to take reflecting the interdependence of UK and US security agencies.

Notably, while the UK remains subject to the European Convention on Human Rights, it is no longer a party to the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, so any legal challenge to a new UK-US arrangement would be on a different legal basis.

Of course, this would create another set of knock-on effects if the UK were to lower barriers to US data transfers while the EU continues to raise them.

If I had to put my money on the eventual outcome, it would be that this will be settled in some form of trade-like negotiations between the EU and US.

There is a growing basket of issues related to online services – as well as data flows, taxation of digital services is high on the agenda on both sides of the Atlantic, and there is a need to coordinate on competition actions.

At the moment, we see unilateral action in many of these areas with threats of retaliation from the other side and this causes uncertainty for everyone.

A more orderly approach would be to establish some kind of EU-US ‘Digital Services Forum’ where all of these issues can be discussed.

We can expect to see more court judgements that cast further doubt on transatlantic data flows and increase the pressure from businesses in both the US and the EU to ask for clarity from their governments.

This will then force everyone to pin their colours to one of the masts – 1) accept data flows are going to stop and we will have data localisation, 2) implement US law reform to enable flows, 3) change EU law to permit flows, or 4) (most likely) some mix of 2) and 3).

I imagine there will be very different views amongst people reading this about which position to take, but that there may be more agreement on the notion that this hard political debate should happen sooner than later.

If your goal is to limit further EU-US data flows then you will be frustrated at seeing the flows continue during years of court cases, and you would welcome an explicit EU position that their political intent is to restrict.

If you rather want to make sure EU-US data flows can continue, then you will be concerned that they are suffering ‘death by a thousand cuts’ in the courts, and want to see both sides working to reconcile their legal codes.

And if you are a business caught in the middle of all this, you want to see both the EU and the US agree on a common path, whatever this may be, so you can direct your organisation accordingly.