I have been thinking about the regulation of online political advertising as this is already a controversial issue, and only likely to become more so in the run-up to November’s US Presidential Election.

Many people in the tech industry, politics, and civil society have also been pondering this subject and coming up with proposals, and I have read many of these with interest.

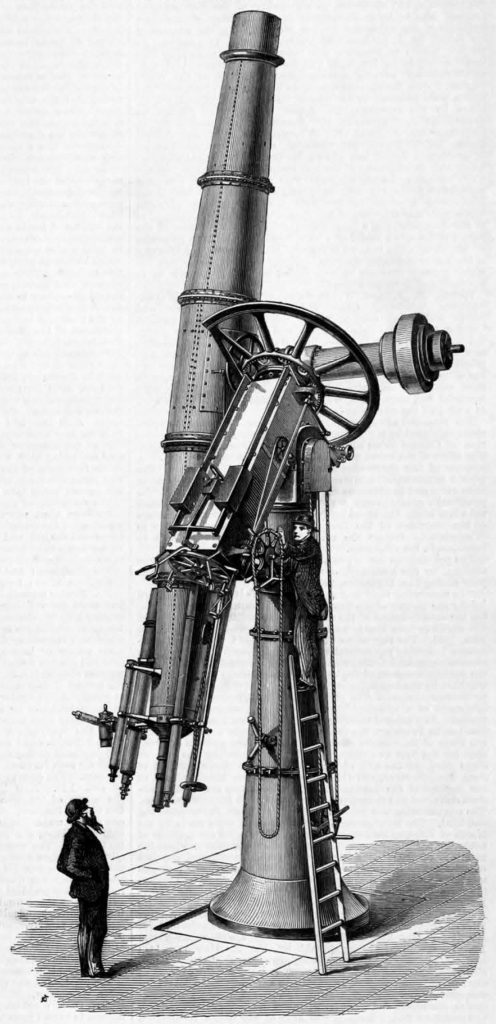

But sometimes, when you are thinking an issue through, you realise that you have been looking through a telescope from the wrong end.

We have tended (myself included) to take as our starting point what we think the rules should be for online political ads, and then to move on to consider the electoral implications.

In this post, I will set out why I think we need to reflect first on how our electoral systems are intended to work, and only then to think about how online political ads fit into this framework.

POLITICAL UPGRADE?

Many of the ideas for how we should control online campaigning reflect aspirations for how politics could be improved :-

- We think it is unfair that politicians can “buy” their way to victory, so are attracted to banning ads to limit the use of money to increase the reach of campaigns,

- We do not like the fact that politicians mislead, so see an opportunity to introduce fact-checking of the content of ads,

- We find it problematic that campaigns are won and lost in battles over small numbers of voters in swing territories, so want to limit ad targeting options,

- We worry about voters being swamped with information around critical times like polling day, so consider ways to limit ads at certain moments.

I want to be candid that I am personally sympathetic to many of the criticisms of how politics is conducted today, and I can see the attraction in using online ads as a wedge to force change, but…

… there are pragmatic and principled reasons for thinking it would be a mistake to allow the online political ads tail to wag the electoral system dog.

The pragmatic objection is that unless there has been broad agreement, preferably enshrined in legislation, for changes to the overall system, then campaigns will just seek to work round any limitations that have been imposed unilaterally.

The principled objection is that making changes that are inconsistent with an overall electoral framework risks undermining election integrity.

ELECTION INTEGRITY

Fears that new rules might undermine election integrity may appear counter-intuitive to those who feel that it is the online political ads themselves which are an integrity threat, so I will unpick this first.

Elections with integrity are based on the democratic principles of universal suffrage and political equality and are professional, impartial, and transparent in preparation and administration throughout the electoral cycle.

Their outcome is not just legally beyond reproach but the process and its outcome are also perceived as legitimate by the electorate.

Kofi Annan Foundation, 2012.

There are two components to election integrity – we need to look at both the design of the electoral system, and how it is implemented in practice.

We see many different political and electoral systems around the world and none of them can claim to be the single perfect model.

Some countries allow huge sums of money to be spent in large, lightly controlled, campaigns where everyone can pile in, while other countries restrict participation and only allow modest sums to be spent on specific, authorised activities.

We will all have views on the models we prefer as citizens (or as political participants) and may robustly attack different systems for their perceived flaws and unfairness.

Some nominally democratic countries have systems that are so stacked to favour certain parties that they are considered neither free nor fair.

In extreme cases, countries may produce electoral outcomes which are not respected either domestically or internationally.

More typically, electoral systems produce results that most people feel should be respected even if they are highly critical of the process and/or its outcome.

If an electoral system has passed this baseline test of being sufficiently free and fair, then the other element we need to consider is whether any particular contest under that system is up to scratch.

The test here is whether the election was carried out correctly within the expectations for the system that applies in that country at that time.

Where this is the case, then an outcome may be highly contentious and continue to be contested long after the event, but people will still consent to be governed by the winning faction – the election has sufficient integrity.

Where the integrity of an election has been fatally compromised, then people may withdraw their consent to be governed, and we fall into crisis.

There have been significant questions raised about the integrity of the 2016 contests in the UK and US.

Many people have strongly opposed these outcomes, but they have not withdrawn their consent to be governed by the winning factions.

The ultimate risk for policies in relation to online political ads is if these lead to a belief that the integrity of an election is so undermined that it should be disregarded.

There are critics who believe we came close to this point with the online activities of the 2016 campaigns, and this motivates them to call for new restrictions to be imposed.

But any changes in response to these calls to action can create new risks.

If important rules are changed outside of a formal regulatory process then this may become a focal point for people rejecting an election outcome.

The challenge is to calibrate any moves carefully so that they do not feed a narrative around the election outcome being unreliable.

In this calibration, the yardstick against which actions should be measured is the prevailing set of electoral laws and norms, warts and all, and not anyone’s view of an ‘ideal’ electoral system.

The integrity test is whether an election was carried out in accordance with the established framework, and so any significant misalignment between the law and new platform or sectoral rules is high risk.

The fact that a platform has ‘good’ motives for being at variance with existing electoral rules may cause some to side with them but does not absolve them of the integrity risk.

I want now to look at some of the aspects of electoral systems that are most relevant for online political ads, and have put these into five categories – Money, Marketing, Data, Controls, and Culture.

[NB a bonus point for spotting why we might think of these as “$2,700” questions].

MONEY

Much election regulation is in reality financial regulation, with detailed provisions about the income and expenditure of campaigns.

There is significant variation in campaign finance rules between countries, so we see massive money campaigns in some countries, like the US, and much more (intentionally) constrained ones in others, eg many European countries.

There is no single right answer to the question “how much money should be spent in election campaigns in a healthy democracy”.

I am at the hair-shirted end of the spectrum (in part because I hated having to go round asking people for money as a politician) and would advocate for more controls.

But I can recognise that this is only one way to see the world, and that money may play a different role in other countries’ systems.

Notably, for the US, there is a sense a candidate’s ability to raise money is a meaningful demonstration of people’s confidence in them, especially during the primary process.

I know there are many voices in the US who would support a less cash-heavy form of politics, but reform would require more extensive re-modelling of the system than simply tinkering with limits given the role that money and fund-raising play.

It is not just about the money as cash but about a set of values and practices that are linked to fund-raising and donating as forms of political expression.

Other countries expressly try to break the link between money and political expression by providing state funding to campaigns.

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASIDE I once introduced a new law to the UK that criminalised the sale of looted archaeological finds. A participant in the debate from the US made a contribution that has stuck with me. In his view, the US had a more open market in artefacts because of a belief that those willing to pay the most for something will do the best job of looking after it. This ran completely counter to the UK/European view of the situation where we were using the law to try and remove the resale value from objects in the expectation that this would get them into public museums. My instinctive reaction was to be offended by the US model as described but over time I had to recognise that there was a logic to it. It depended on the whole system being oriented around this big money idea of protecting antiquities, with incentives for buyers to move objects to museums that were themselves big money institutions. The variance in attitudes towards money are huge between these two different systems but each works in its own way. We can see parallels to this in politics with Europe trying to suck the money out and trusting state-funded politicians, while in the US there is a sense that politicians who can raise more money will do a better job when in office.

Funding rules may also be used as a tool against foreign interference by prohibiting campaigns from accepting donations from people outside the country.

A major consideration for our topic of online political ads is then the scale of money permitted in a country’s political system.

Where a country has a big money system, and there is high internet usage, then the logic of the system points to spending a lot of money online.

This may be tempered by restrictions on specific channels that I will look at in the next section, but we might expect big money systems also to be more permissive in the forms of marketing that they allow.

The whole point of campaign funds is to capture voter’s attention for the campaign’s messages so it would be an odd system that gives you permission to spend a lot of money but then heavily restricts the channels to voters.

MARKETING

There are different views between countries on the desirability of marketing generally – do you think ads are a great way to connect discerning consumers with products and services they might want, or are they a way to con gullible people into buying things they do not need?

These general feelings about marketing then have an additional overlay of views about how political campaigns should use marketing tools.

The US has generally been positive about the value of marketing, and very permissive in allowing political campaigns to use the full spectrum of tools including broadcast media.

France provides an interesting contrast in taking a more sceptical approach to marketing generally, and in applying a blanket ban on all paid-for political marketing in the three months before an election.

Twitter moved to ban political ads on its platform in November 2019 with a policy that expressly declares political marketing (at least on their platform) to be a ‘bad thing’.

Twitter globally prohibits the promotion of political content. We have made this decision based on our belief that political message reach should be earned, not bought.

Twitter Political Advertising Policy

Facebook by contrast permits political ads (subject to general terms that require all advertisers to comply with any relevant local laws) and so appears aligned with the view that it is OK for ‘political message reach’ to be ‘bought’.

Twitter’s policy is inconsistent with the norms of the electoral system in the US which permits campaigns to buy reach across multiple channels..

This inconsistency may not become a major issue if only Twitter takes this position, but it could become very problematic if other platforms, notably Facebook, were to take the same view.

Conversely, people in countries like France may feel reassured by Twitter’s position, and have concerns that Facebook’s global support for political ads is not aligned with their local norms.

If you accept the view that misalignment with an electoral system creates an election integrity risk, then the preference should be to conform with each prevailing local model.

In France, this would mean demonstrating a real commitment to prevent political ads as these conflict with local norms, while in the US that would mean not excessively restricting an activity that is consistent with local norms.

DATA

You might get the impression from the Cambridge Analytica scandal that something entirely new was happening here in terms of political campaigns profiling voters.

I certainly do not want to play down the seriousness of that particular use of data, but anyone who works on political campaigns would see this as part of a much broader pattern of campaigns using data.

Cambridge Analytica’s work was aimed at adding some more data fields to US voter databases that were already groaning with information used to profile voters, and which have continued to grow to this present day.

The UK does not run political campaigns at the scale of the US, but I thought it might be helpful to reflect on the experience of my first general election campaign in 1997.

CAMPAIGN LIKES IT'S 1997 For the 1997 UK General Election campaign, we had a voter database called EARS (Election Agent Record System) that ran on MS-DOS. This was populated with the local register of voters which all parties could obtain in various wacky formats that had to be converted before use. The bread and butter of our campaigns was to knock on people's doors, or more rarely then phone them, and ask for their voting intention which went into the database. Over the years, you would build up a history of how people said they would vote and could put them into quite specific categories based on these patterns. We were able to add whether people had interests in key issues like health and education by encouraging them to return paper survey forms to us. We used people’s names to predict whether they were likely to be elderly (back then, we were fairly certain you were over 60 if you were a Hilda or an Arthur, though you get caught out when name fashions cycle round too quickly!) We might predict whether people lived in social or private housing by looking at their front doors as we walked down the street and use these to build ‘lookalike’ categories (local authority housing tended to have the same standard doors). All of this data was then used to generate person and interest specific targeted letters and other communications throughout the campaign. We strongly believed that it was this targeting approach that led to a 15% swing and victory in the election.

I may sound like an old git waxing lyrical about the good old days, but I tell this story to make the point that if targeting works, as it does, and it is not prohibited, then campaigns will do it using whatever tools they can get their hands on.

The new targeting tools offered by social media platforms are of course orders of magnitude more powerful than the options we had back then, and they can run on data that the campaign hasn’t necessarily had to collect themselves.

But if tools like Facebook’s were not available, and all other conditions remain equal, then I have no doubt that other similar methods would be developed using first and third party databases.

If the problem is with interest-based targeting, then limiting access to some online ad tools may achieve a temporary disruption but lasting change requires a change in the rules of the electoral system, either through cross-party agreement or with legislation.

If the concern is with geographical targeting because of worries that elections are being excessively decided in narrow swing districts, then this requires a much broader look at how an electoral system works.

If the issue is that with campaigns having too much sensitive political data, then we need to look at data protection and privacy law and how this applies to political parties collecting and using voter data in any form.

There is an understandable pressure for platforms to ‘do the right thing’ and impose their own limitations on how campaigns can use data, but there are risks in platforms getting too far out ahead of electoral rules and norms.

The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office has produced a good overview of the data issues in political campaigns with proposals for how to address these within an EU/UK law framework.

CONTROLS

There are many different models for how countries apply controls over who can participate in their electoral campaigns.

Campaign finance regulation is a common form of control, imposing a set of criteria for who can spend in an election rather than necessarily over who can speak.

It is common for there to be rules requiring parties and candidates to be registered in some way, and to prove they are of good standing before they can enter a campaign.

There may also be transparency requirements in respect of both campaign finance and the identification of who is promoting campaign messages.

These controls can be contentious generating concerns that overly prescriptive regimes shut out too many potential participants, or that overly permissive ones allow too much scope for “off-the-books” activity that can influence an election.

The set of controls in each country is an integral part of their electoral system as a whole, and they will usually be revisited on a periodic basis when electoral law is updated.

There are concerns in some countries that their electoral law is out-of-date and does not take into account the availability and use of online political ads.

This is especially true in the US and UK where politicians have failed to update their electoral laws in spite of claims that they had proved inadequate in the 2016 campaigns.

The UK Parliament’s DCMS Committee called for UK law to be revised in July 2018 but there have not been any changes to date so that the December 2019 General Election was fought under the same rules as previous campaigns.

In the US, an attempt to update the law was made with the Honest Ads Act as far back as October 2017 but this has also not led to any actual legislative changes ahead of the 2020 campaign.

Politicians in other countries have been much more effective in updating their laws and create new regulatory frameworks for online political ads.

Brazil revised its law in 2017 so that new rules would be in place for their 2018 elections and Canada updated its legislation ahead of their 2019 General Election.

In some cases, existing legislation is written in such a way that revisions may not be as urgent, for example electoral law since France bans all forms of paid promotion across all media it does not need to make explicit mention of online ads.

The interaction between services offering online ads and these controls can be a very challenging area, especially as it has to be considered on a country-by-country basis.

If a country maintains registers of eligible campaigners this can make it much easier for platforms to verify whether someone is a legitimate political advertiser.

On the other hand, a country may apply eligibility criteria that are very difficult for a platform to follow.

For example multiple independent campaigns may be permitted in the UK but not if they coordinate with each other in ways that the law forbids.

The public authorities have a hard enough time defining what constitutes illegal coordination as we see in an enforcement action following the 2016 Referendum where the courts overturned a decision by the UK elections regulator.

Where the law is as complex as this, it will be much harder for online ads services to determine eligibility than a simple “check if they are on a register” model.

Controls related to transparency may again vary widely in their ease of implementation.

Where the requirement is for data that is already being collected by platforms, and they have tools to provide this in accordance with the regulation, then this may be straightforward.

But where extensive customization would be required, or the compliance risks become too high, then platforms may decide not to offer their services at all as happened with Google in Canada.

In each case, the preferred outcome should be that there is close alignment between the controls that the legislation envisages and those that platforms apply in practice.

Platforms have the option to withdraw their services but even this will typically require them to implement controls as they need to define and identify the right class of political advertisers in order to enforce any ban.

CULTURE

As well as formal rules for elections, each political system has its own culture and modes of behaviour.

There are two aspects in particular that are important for our consideration of online political ads – inter-party cooperation and political messaging norms.

In some countries, there is a sense that political parties are members of the same club and there can be high degrees of cooperation between them.

This can have a significant impact on their behaviour and the way in which they run their campaigns.

For example, Danish political parties signed up to a code of conduct in the run-up to an election in 2019 and worked closely with the government and each other.

It is common for there to be formal and informal channels of communication between the people who run election campaigns in different parties that can be very effective ways to resolve issues.

There may be parties who are excluded from the ‘club’ by the other parties because their political orientation is considered too extreme, and parties may themselves sometimes seek exclusion as they style themselves as ‘anti-establishment

This can lead to a situation where the main parties on both sides of the political spectrum are following a shared set of norms and codes of conduct, while facing off against other parties who pride themselves on playing by different rules.

If the ‘outsiders’ are seen as being more effective in their use of online political ads than the ‘insiders’ then this may stimulate demands for increased regulation and new restrictions.

This dynamic can create strong pressure to act especially where the outsiders are promoting an unattractive form of politics and this pressure may be expressed in overtly partisan terms.

Once the argument has been made that a platform should do something in order to disadvantage (or remove a perceived advantage from) particular political factions, then this creates a very challenging situation for platforms.

You can read more of my thinking about these questions in a previous post on partisan political effects.

We see demands for new controls to be applied to the content of online political ads especially where there are more heated, partisan contests.

The controls could involve platforms refusing to accept political ads if they contain prohibited messages, or they could refer ads to 3rd party factcheckers and reject or treat the ads differently based on the factchecker judgement.

The key question to consider in relation to such proposals, is consistency with the prevailing culture around political campaign messaging as a whole in a particular country.

There are significant variations between countries as to what is considered acceptable in political discourse.

The outer edges of acceptability may be enshrined in law such that parties or candidates could be prosecuted if they use messages that are considered defamatory or illegal hate speech.

Within these outer, legally-defined edges, there is a broad space that is governed more by the norms of local political culture.

For example, in the UK it is common for parties to make exaggerated claims that could be considered caricatures of reality.

These claims will be based on some facts, however tenuous, to avoid the perception that they are outright untruths as bare-faced lying still has the capacity to harm a campaign.

Other countries will calibrate this differently with UK-style exaggeration seen as going too far in some political cultures, while others will go even further and have fewer scruples about supporting claims with facts.

It remains the case that in most instances challenges to political claims are reactive rather than there being pre-moderation of these claims.

Politicians make their campaign claims in statements to the media, in their direct mail and posters, and using online channels without hindrance, and are then exposed to scrutiny, challenge and correction.

Political cultures evolve and it is interesting to see the growth of and interest in factchecking of political claims over recent years, including ideas for real-time factchecking.

If this leads to a situation where fact-checking becomes the norm for all campaign activity across all channels, then this creates the conditions for it also to be applied to online political ads.

A process of reviewing norms around claims in political campaigns generally, not just online, may lead to new standards that are broadly applicable and broadly accepted.

The challenge with changing the standards for online political ads in isolation, however immediately attractive that may feel, is that this will not be sustainable without the broader cultural shift.

It is also possible that the desire for change here is part of a ‘rationalist delusion’ and that people are not keen to change the status quo around political messaging as this appeals to their intuitions.

If this is the case then it is not clear that attempting to force change would be successful in its own terms of improving democratic decision-making.

I would recommend Jonathan Haidt’s ‘The Righteous Mind’ if you, like me, have generally seen politics as about people making fact-based rational choices, but have accumulated experiences that call this into question.

SO WHAT SHOULD HAPPEN?

Shakespeare, Henry IV part 1, Act 5 Scene 4.

If it seems like I am arguing for platforms to be followers rather than leaders when it comes to the rules for online political ads, that would be an accurate summary – this most sensitive topic requires more discretion than valour.

It is healthy for platforms, and the people who work there, to take a view on what good rules look like, and they may choose to advocate for this, as Facebook did, for example, in supporting the Honest Ads Act in the US.

But bold unilateral steps to change the rules of the game should ring alarm bells, especially where they appear to be responsive to only one of the parties in an election.

The recent call by the Joe Biden campaign for Facebook to take unilateral measures is one such alarming moment.

This is not to argue that the proposed measures do not have merit – they are interesting and worthy of debate – but that they are being played into the wrong forum.

If these are serious ideas for how US election campaigns should be conducted, then the Biden campaign should first pitch them to the Republican party to see whether they agree.

You may laugh at this suggestion and wonder what I am on, but this is not meant to be facetious – platforms cannot consider proposals like these without the views of all the key players, even (or especially) if these are hostile.

When legislatures consider changes to electoral law they will get a wide range of input from political parties, civil society and other relevant experts.

The views of all of these people will normally be put into the public domain and form part of a debate in law-making bodies and the media.

Such a broad public consultation and deliberation is a good discipline to apply to all calls from politicians or civil society for platforms to make changes impacting elections that go beyond legal requirements,

Platforms should also engage in broad consultation exercises whenever they plan to make unilateral changes of their own in respect of political ads.

A deliberative process may still leave some participants unhappy with an outcome, but it will help to surface election integrity risks early and ensure they are explored rather than ignored.

I want to close with an example of good practice, where there are meaningful proposals for change, but these are rooted in the electoral system as it is rather than assuming it can be rewritten around online political ads.

The UK-based campaign group WhoTargetsMe recently published their Ten simple ideas to regulate online political advertising in the UK.

The article sets out a series of practical measures that would collectively build up a new regulatory framework for online political ads in the UK.

I would not necessarily agree with detail of all the proposals they have put forward but this is exactly the kind of work program that could deliver results without creating unnecessary election integrity risks.

A PS RE THE US

A final thought is that platforms should be careful not to consider the US as a model for the rest of the world when it comes to online political ads.

The US is a real outlier in terms of all of the areas I touch on above :- obscene amounts of money, all marketing channels open, profligate use of data, a weak elections regulator, and a culture of warring parties prepared to say almost anything.

US-based platforms will naturally prioritise developing solutions for the US market, and much of the rest of the world feels they have a stake in the outcome of US Presidential elections.

This is especially true in 2020 where millions of people around the world feel they have been pulled into the psycho-drama of the current contest.

There will be elements from the US experience that will be useful elsewhere but it would be a mistake to think that systems can be rolled out across the world wholesale.

The starting point has to be a needs analysis for each country that looks at how their local political system thinks about Money, Marketing, Data, Controls and Culture.

This political analysis should shape the solutions that are built, even if it is hard and expensive for platforms to have to customise for each country.

Summary :- I put questions about the regulation of online political ads into a framework of general election regulation. I urge caution in terms of unilateral moves by any party. I suggest how progress can be made but only through broad consultation and deliberation.