This is the third of three posts exploring some of the challenges around managing misinformation on social media.

My goal for this series is to tease out some of the underlying motivations that shape the regulatory approaches of both governments and platforms.

If we can understand the real drivers we can make more sense of what is happening than if we assume this is a simple battle between truth and falsity.

In the first post, I talked about the aversion for platforms of becoming involved in partisan debates.

In the second, I roamed more widely than just misinformation and developed a framework for the different ways in which social media has partisan effects.

In this post, I will look at how governments are responding to these partisan effects with regulatory measures of their own.

Politics and Sedition

There are two key propositions that I think help us to understand regulatory responses to misinformation.

Misinformation is commonly used as a form of expression by people with seditious political intent.

Regulation of misinformation sits within a broader context of attitudes to and controls over seditious speech in a society.

I have chosen an old-fashioned word, seditious, to describe political discourse that does not follow the usual niceties (as it does not respect them), but falls short of the calls for political violence we might label as ‘terrorist’.

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward insurrection against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent towards, or resistance against established authority. Sedition may include any commotion, though not aimed at direct and open violence against the laws. Seditious words in writing are seditious libel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedition

I am not proposing a simple 1:1 relationship where misinformation is the exclusive preserve of the seditious, but do see a particular affinity between seditious intent and misinformation.

Where the ‘establishment’ claim truthfulness as one of the values that defines them, then falsity itself becomes a potential weapon for those who reject and wish to undermine that establishment.

We see this phenomenon playing out in real-time as those who oppose government actions on Covid-19 have taken up conspiracy theories as part of their protest narrative.

These protesters are not more ‘stupid’ than other people, they are rather more seditious.

If the diagnosis is ‘stupidity’ then we would look to education and getting the facts out there as a cure, and this is where a lot of effort goes today.

But if the diagnosis is ‘seditious’, then not only will forced education by the establishment that is being rejected not change minds, it may actually be counter-productive.

Seditious speech is much broader than misinformation and will usually involve real grievances and fact-based claims against those in power.

And there are, of course, instances where the establishment themselves use misinformation and they should certainly not be let off the hook.

More authoritarian regimes may control the information environment to such an extent that they can, at least within their borders, present misinformation as truth and sustain the falsehood.

In more open societies, checks and balances, not least a free press, mean that the authorities at least have to maintain a facade of being truthful, and make some (even if grudging) corrections when found to have misled.

Path to Regulation

When governments are considering regulation of misinformation, this is typically framed as a truthful establishment seeking to hold off people trying to undermine them dishonestly.

Their case for regulation is made within the general framework of considering where limits should be put on speech as set out in international human rights conventions.

Article 19

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

I will consider the special case of the United States later, but most countries in the world have significant bodies of law in place that limit speech precisely on the grounds set out in 3(a) and 3(b) above.

Laws may suppress both true and false speech if this is deemed to be a necessary and proportionate response to the threat.

Within this broader framework, regulation directed at misinformation may feel more justifiable, and therefore defensible, than regulation that restricts speech purely on the basis of its political intent.

From the perspective of the seditious speaker using both truth and false statements to attack the state, this distinction may feel less material than the simple fact that they face sanctions.

As I describe examples of regulation below, I recognise that politicians may also have other public interest goals even if I am focused on their anti-sedition motivation.

Politicians may support a defamation law, for example, both because they care about private citizens suffering damage to their reputations, and because they see this as a tool to prevent seditious libel.

Examples of Regulation

I have selected some examples of regulatory responses that help to illustrate approaches to sedition and misinformation.

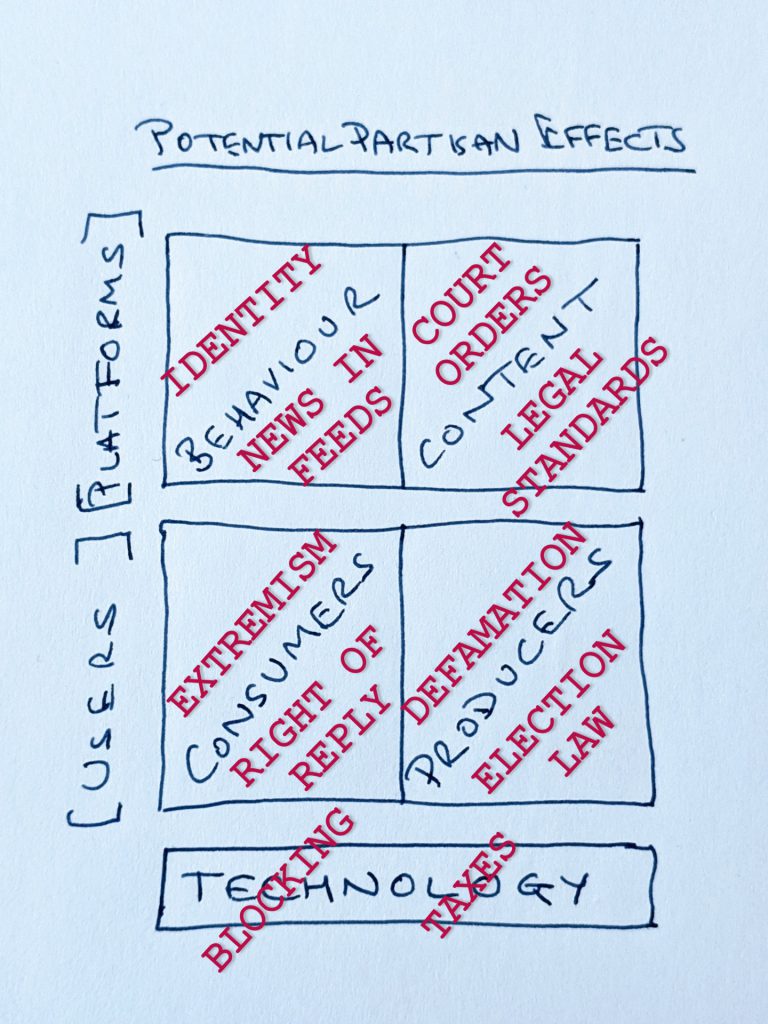

In a previous post, I described the different places where partisan effects may happen on social media services.

I have overlaid my framework with text in red in the figure below to show where different regulatory tools are being used to control political speech.

I will spend the rest of this post working through examples of regulation and their effects from the bottom up.

TECHNOLOGY

Governments may use telecoms regulation to block all or parts of the internet (and cite misinformation as one of the justifications).

Fiscal measures may also be used to discourage the take-up of social media technology.

I described previously how the widespread adoption of social media can create a partisan effect in favour of less well resourced and excluded factions.

In many cases, this will be unexceptional as new citizen groups organise and engage constructively in the political process.

In other situations, the growth of factions outside the mainstream may be deemed seditious by those in power today.

The simplest way to reduce any advantage these factions gain is to roll the technology back by blocking either social media or the whole internet.

The record of blocks show us that they are commonly used during election periods or at times of social stress with the rationale of preventing disorder.

The public rationale for a block may be to prevent the circulation of misinformation but its impact is to prevent access to all information.

There may also be very real problems of violence, going beyond sedition and into terrorism, that the blocks are intended to reduce.

The economic and social cost of blocking the internet, or parts of it, is clearly going to be significant for societies so this is not usually a first choice option.

While blocking seems to have been considered but decided against in the UK during riots in 2011, it seems highly unlikely that a UK government would decide to block large services today but it is not entirely unfeasible.

We do see blocks even in countries where there is high internet usage like Turkey, but the political risk for governments of imposing long-term restrictions on key services is likely to increase with internet adoption.

As well as ordering internet service providers to implement physical blocks, governments can use pricing mechanisms to reduce the take-up of new technologies like social media.

The so-called ‘gossip tax’ introduced by the Ugandan government in 2018 is an example of this approach.

This measure created a special charge for people in Uganda using social media services that had to be paid on top of the usual internet access charge.

The Ugandan government made a fiscal argument for their measure that is consistent with the concerns many countries have about the unfair distribution of tax revenues from online services.

But it seems clear that the President also expressly wanted to discourage social media usage which he saw as often being seditious.

“It’s actually political speech and online organising which has real-life implications for him and his power. The overarching intention is to stifle free speech, especially now there is evidence that online organisation works.”

Lydia Namubiru, Ugandan activist to The Guardian, June 2018.

Other countries have considered the Ugandan model of taxation targeted at social media services and some later backed down in the face of opposition from local and international activists.

Blocking internet services remains common in some countries but these are increasingly being monitored and challenged, for example by the Software Freedom Law Centre in India.

For many governments, these options to tackle seditious content by rolling back the use of social media through blocking or taxes are not realistic.

They are instead allowing social media technology to be used and looking to other areas where it can be controlled as we will now explore.

USER (AS CONSUMER)

It is rare for governments to make the simple consumption of content illegal except in cases of extreme harms.

There is interest in using regulation to require consumers who have consumed false content also to consume any corrections.

Any form of possession of child sexual exploitation material is illegal in most countries making its consumption criminal with few defences.

In the political context, the possession of material deemed to be terrorism-related may similarly be criminalised and users made liable if they consume this content.

Questions about the scope of content that should be included in terrorism prevention prohibitions and the extent to which strict liability should apply to ‘extremism’ are a matter of frequent debate.

Where political content does not fall within some kind of violent extremism definition, it seems unlikely that simple consumption will be criminalised.

Regulation tends rather to focus on the role of producers and platforms with consumers being the ‘innocent’ victims.

The line between consumption and production can be blurred on social media as people can easily, and sometimes widely, share third party content.

It is important for regulations to create clarity about when a user should be treated as a consumer and when they have crossed over to become a producer and existing legal definitions do not always fit well.

I will write more comprehensively about these questions in a later post as they are especially important in the political arena.

Right of Reply

One area that is widely discussed is whether misinformation could be corrected with some form of ‘right of reply’.

This idea does not criminalise the consumer, but instead requires them to consume ‘good’ content if they have consumed ‘bad’ content.

We see precedent for this in existing frameworks for media regulation and in court-ordered remedies in defamation cases.

It is common for newspapers to carry a correction to a story that has been complained about, and for people losing defamation cases to be required to to confirm publicly that they said something wrong and libellous.

These models can also apply in the social media world so that content producers would publish their own corrections or admissions of libel.

These corrections would then reach people ‘organically’ relying on a platform’s normal distribution mechanisms to deliver the correction to the content producer’s followers on social media.

Some policy makers have seen an opportunity go further by requiring platforms to implement special mechanisms to ensure corrections get to people who saw the original content rather than relying on organic reach.

We see this latter mechanism in section 21 of Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 which can be used to make platforms to push correction notices to relevant people in Singapore.

The actual impact of showing corrections to people is not clear but this idea seems to hold a strong appeal for many politicians.

The appetite for these mechanisms may change as research evidence emerges over time to show whether showing corrections makes people more or less seditious in practice.

USER (AS PRODUCER)

There is a significant body of existing law that governs content producers in most countries around the world, including prohibitions on misinformation.

There are questions around enforcement of these laws and addressing these might be more effective than creating new specific regulations.

Defamation

Defamation laws are long-standing regulatory responses to deal with misinformation that is intended to cause harm to a specific person (or organisation where these are included).

Political defamation is often considered to be a particularly serious offence, eg this from the German Criminal Code :-

Section 188

Malicious gossip and defamation in relation to persons in political life(1) If an offence of malicious gossip (section 186) is committed publicly, in a meeting or by disseminating material (section 11 (3)) against a person involved in the political life of the nation due to the position that person holds in public life and if the offence is suitable for making that person’s public activities substantially more difficult, the penalty is imprisonment for a term of between three months and five years.

(2) Defamation (section 187) under the same conditions incurs a penalty of imprisonment for a term of between six months and five years.

German Criminal Code

While many countries offer additional protections for politicians, the US has instead made it harder for public figures to win defamation cases with the Supreme Court judgement New York Times Co. vs Sullivan in 1964.

I will discuss US exceptionalism more in a later section but the important point to note here is that some of the political misinformation that most causes concern in the US is likely already illegal in much of the rest of the world.

While defamation law may quite clearly prohibit certain forms of misinformation, enforcing it in the context of social media can be difficult because of the challenges of scale and speed.

Judicial processes can be slow relative to the ability of people to spread content (often for the good reason of wanting a full picture of the facts before the court reaches a judgement).

The processes are also typically designed in anticipation of a small number of actions against large content producers rather than being suited to a very large number of actions being taken against individual content producers.

We have seen creativity in the use of existing legal processes in a case in the UK where a politician pursued people who shared defamatory comments on Twitter seeking small scale remedies.

While many people have concerns about defamation laws, especially where these come with criminal sanctions and/or where the bar is set too low, they have the merit of being legally mature.

If new regulatory measures are to apply to misinformation that is aimed at discrediting politicians then there is a risk of confusion if they do not at least follow the same legal principles that a country applies to defamation.

The protections offered by defamation law are not specific to politicians, and their use is limited to misinformation that targets named people.

For example, they might be used against the claim that ‘politician A is deliberately pushing a killer vaccine’ but not to the claim that ‘vaccine A kills people’ (where these are both demonstrably false).

Claims of this more generic kind may fall under other existing legal regimes where they are being played into the political arena.

Electoral Law

Most countries have laws related to the conduct of politics and elections that may already create regulatory constraints on political misinformation.

For example, a provision under UK electoral law allows for a candidate to be disqualified for spreading misinformation about other candidates, and this was used as recently as 2010 to remove an elected Member of Parliament.

UK law also requires political factions to register with a central authority and to include contact details on printed campaign material,

To date, this requirement has not applied to digital material, but the UK government has committed to updating the law to require ‘digital imprints’.

Electoral law requirements like these do not necessarily speak directly to the truthfulness of political content but are highly relevant in terms of managing the spread of political misinformation.

If a faction were to engage in significant political activity without identifying themselves to regulators and meeting relevant legal requirements then the tools are there to shut them down.

Enforcement generally depends on the offending faction being within jurisdiction so these may be a weak safeguard against foreign interference.

But in most political contests, the largest and most invested factions will be domestic and can be made to comply.

Advertising

Content producers, of all types, usually face additional regulation when they are using paid-for advertising and this may include truthfulness provisions.

Regulatory regimes differ between countries with standards often developed and enforced by industry bodies.

The advertising code in the UK is managed by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) and includes this provision :-

3.7 Before distributing or submitting a marketing communication for publication, marketers must hold documentary evidence to prove claims that consumers are likely to regard as objective and that are capable of objective substantiation. The ASA may regard claims as misleading in the absence of adequate substantiation.

UK Code of Non-broadcast Advertising and Direct & Promotional Marketing (CAP Code)

This looks like, and is, a prohibition on misinformation in advertising which would stop someone promoting a message like ‘5G Causes Covid-19’ unless they could substantiate this with evidence.

Subject to the usual questions of speed and scale, this regulatory mechanism means there is already a tool in place to deal with promoted misinformation.

But there is an important carve-out for political campaigns that is worth noting as it shows the regulator shares the concerns about partisanship that I described in relation to the platforms.

7.1 Claims in marketing communications, whenever published or distributed, whose principal function is to influence voters in a local, regional, national or international election or referendum are exempt from the Code.

UK CAP Code Scope

In other words, political campaign material is exempt from the entire set of advertising standards including those related to truthfulness.

A commercial advertiser saying their soap ‘washes whiter than other soaps’ could be asked to prove this, but a political party saying they would ‘give everyone free money whilst cutting their taxes’ would not.

This is not intended to be special pleading for Facebook who have been on record saying they also do not want to regulate the content of political ads.

But if there is a will to regulate political ads for truthfulness then we might first want to consider using an existing regulator rather than have platforms do this.

I would note that ASA might be horrified at this even being suggested and further reflection might lead to other regulatory tools than asking either the platforms or the ASA to adjudicate on the content of political campaigns.

As a ‘fun’ example of the challenge, see this 1994 Election Broadcast by the Natural Law Party that claimed ‘scientific studies’ showed the UK’s problems could be controlled by ‘yogic flying’ (UK broadcasters had to show this by law).

Content Producer Summary

When we look at both defamation and electoral law there are a number of existing provisions that are applicable to challenges around misinformation.

There is wide variation between countries in the extent to which their versions of these laws will restrict content producers., with this settlement shaped by local attitudes to acceptable and prohibited political speech.

Amendments to existing legal texts governing content producers and the systems for their enforcement are likely to be a key part of the political response, but there are also important constraints.

These constraints drive some governments to skip over enforcement against individual content producers and instead to consider how they can require platforms to do the work for them.

This is what I will consider now in the final two sections.

PLATFORM (BEHAVIOUR)

There is debate around requiring platforms to collect more personal identifiers as a means of controlling misinformation.

There is interest in platform feed algorithms though no country has yet legislated to impose their own controls.

Identity

I described in an earlier post how platform identity requirements might have partisan effects on unpopular and/or excluded factions.

Some politicians have become interested in strong identity requirements as a tool against seditious speech often citing the need to control misinformation.

Russia passed its so-called ‘Blogger’s Law’ in 2014 that requires social media users with more than 3,000 followers to register with a state regulator and sought help from platforms for this.

Austria proposed a law in 2019 that would require platforms to collect identifiers, including real name and address, from all their users.

The Austrian proposal was subsequently dropped but similar ideas continue to be discussed in EU countries and have also been raised in the UK.

Supporters of stronger identity requirements claim this will make it easier to enforce on existing legal restrictions, some of which I have described above.

There is a counter-argument that collecting identifiers from everyone is not necessary as people can be identified by their IP address in serious cases.

This is an area where more work needs to be done to understand the real nature of any problems for law enforcement, and of the impact of government mandated identity collection on political speech more broadly.

Algorithms

There has also been growing interest in the idea of regulating social media feed algorithms.

This is often expressed as a demand for transparency but the opening up of algorithms for scrutiny may be a means to an end rather than an end in itself.

The UK Government commissioned the Cairncross Review to look into the “…challenges facing high quality journalism in the UK, putting forward recommendations to help secure its future.”

The Review team described how there could be regulatory intervention to shape the content of news feeds.

Another option, also considered by this Review, is to oblige platforms to give prominence to high quality or public-interest news, whether in their news aggregation services, in people’s social media feeds, or in search results. This could potentially be combined with a quota or target, requiring that a minimum proportion of the content distributed on specified platforms must be of high quality or specifically public-interest news.

Cairncross Review Report, February 2019

The Review did not recommend immediate regulation but instead to work with platforms under a threat of later regulation if there is not enough progress.

There are obvious challenges for any model where governments decide to preference some news sources over others based on some idea of quality.

With a truly independent regulator, it is possible that such a system might be regarded as neutral and win public support.

But there is a significant risk in terms of both perception and fact that this would come across as government favouring its preferred news sources.

This is a fraught area as any ‘quality’ measure could have significant partisan effects and many people distrust both platforms and governments.

We can expect a period of experimentation using trust ratings from commercial providers and industry collaborations.

This may be followed by government regulation, in spite of the risks, if powerful news media providers remain unhappy with their exposure in feeds and lobby for new measures.

PLATFORM (CONTENT)

Some countries have adopted measures to require platforms to apply government standards to specific items of content.

Governments are interested in forcing platforms to apply their legal standards over any platform standards and one country has implemented this.

Another regulatory approach is for governments effectively to superimpose their content standards on those operated by platforms.

Court Orders

The common way to do this is for courts to order platforms to suppress specific items of content whether or not these breach the company’s rules.

This has been a longstanding practice in areas like defamation and intellectual property where platforms routinely remove content in response to court orders or threats of legal action they deem to be valid.

Election law was amended in France in 2018 to create a new power for judges to require platforms to take measures to prevent the spread of specific items of misinformation.

This power is limited to the three months before polling day and is to be used in response to a complaint from a participant in the election.

Singapore created a law in 2019 that also creates a power to instruct platforms to suppress specific items of misinformation.

The Singaporean law has been more contentious than the French law as the direction power is granted to Ministers rather than judges, it applies all the time not just during elections, and the scope of remedies is broader.

Political support for these kinds of measures will depend on the local culture of tolerance for seditious speech.

France has decided (to date) that giving only a limited power to judges strikes the right balance between freedom of expression and protecting public order.

Singapore has granted much broader powers to its executive consistent with its generally less permissive approach to anti-state activities.

We can expect other governments to consider similar regulations that will be narrower or broader depending on their tolerance of seditious speech.

Legal Standards

As a final example, we can look at the catchily titled Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz (NetzDG) which became law in Germany in 2017.

This was initially framed as an ‘anti-hate speech’ law but is broader in scope than hate speech and was strongly motivated by political considerations.

The context was one of increasing activity by far right political factions during the period 2015-17.

German law contains a number of significant anti-sedition provisions that are intended to prevent the rise of another Nazi party.

These include explicit bans on neo-Nazi factions and symbols as well as measures that criminalise speech that causes social division.

German lawmakers believed that platforms were not effectively enforcing these laws and that this was contributing to the rise of the far right.

The intent of the NetzDG is to force (large) platforms to apply German legal standards in preference to their own standards under threat of sanction.

It was passed in summer 2017 with the support of the large centre-right and centre-left parties in the run up to Federal elections later that year.

The law offers additional protections to private citizens in respect of defamation and insults but its main target was the suppression of the far right.

There was broad support for this approach in Germany reflecting their particular history with only mild opposition from some smaller parties.

Platforms are now required to enforce directly on provisions of German law that have a significant bearing on misinformation.

In particular, untrue claims about politicians may be suppressed for defamation, and false claims about minorities (a key concern in recent elections) may be removed as hate speech.

Platforms generally had provisions against hate speech already (with some differences in definition from German law), but were largely reluctant to enforce on speech directed at politicians.

There has been interest from other countries in this model of layering local legal standards on top of platform content standards.

This may be more controversial where the laws that will be subject to more aggressive enforcement do not accurately reflect local attitudes to seditious speech.

Where local law is already seen as a partisan tool, eg if it criminalises all opposition factions as ‘extremist’, then forcing platforms to adopt these standards would be especially challenging.

AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM

None of the examples I have used involve US regulation, and it is worth reflecting before I finish on why the US is an outlier.

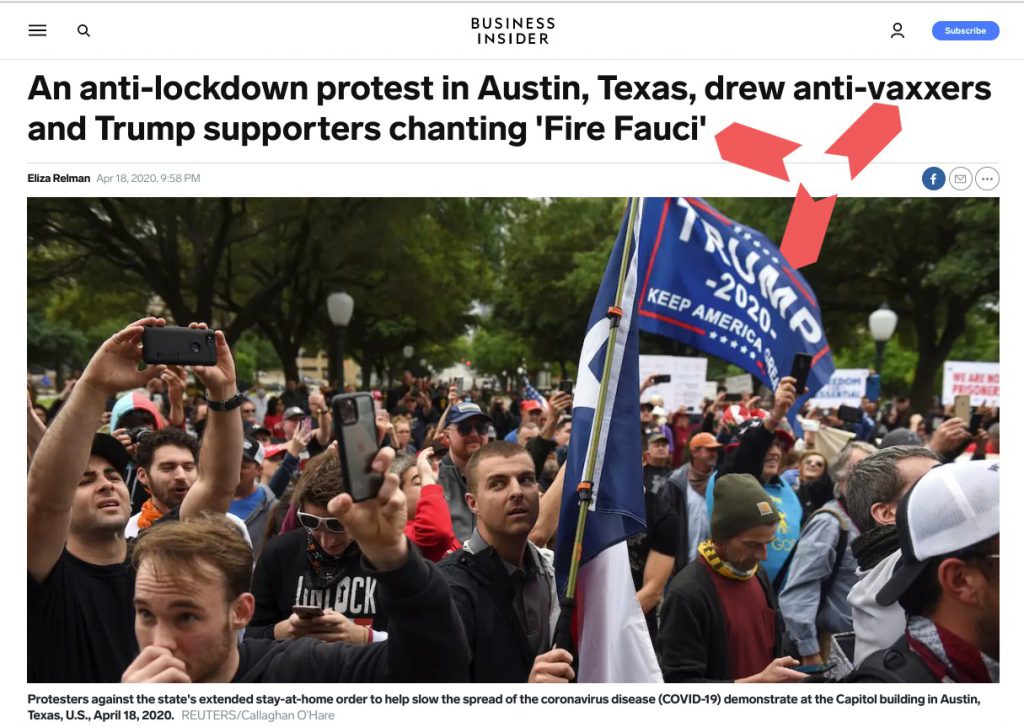

A recent image of armed militia in a US State Capitol nicely illustrates what is special about US attitudes to sedition.

Each country sets its own bar for when seditious activity becomes illegal and in the US that bar is high enough for armed militia to slip under it.

This is not to enter into the gun control debate but reflects the fact that sedition holds a special place in US popular and political culture so that it is not just tolerated but actively admired.

If we take Germany as a counterpoint, sedition is not associated with breaking free from British rule, but with the rise of the Nazi Party who came from outside the establishment to capture and utterly corrupt the state.

So, the starting point for US attitudes is very different from the starting point in other countries and this is reflected in a very different legal regime.

This is sometimes expressed as ‘the US has the First Amendment so everything is permitted’ but the reality is more complex than that.

It is notable that some of the most-quoted statements about the First Amendment come from a dissenting opinion in a 1919 Supreme Court case that did not strike down a then-operative Sedition Act.

The case that defines the modern framework, Brandenburg v Ohio in 1969, did though set the US on an exceptional path in saying the state could not restrict political behaviour that many other countries would routinely criminalise.

The precise boundaries of permitted political speech continue to be revised with further cases such as Holder v Humanitarian Law Project in 2010, but remain much broader than in other countries.

There was until recently broad bi-partisan support for this very permissive approach to political speech.

Just as we saw the two mainstream parties in Germany (CDU and SPD) aligned on restricting seditious speech, so we saw both mainstream parties in the US aligned in opposing restrictions even where they disagreed strongly with the speaker.

From this baseline, we seem to have moved into a new set of circumstances since President Trump was elected in 2016.

The current US President built his support using a seditious narrative positioning himself as an outsider taking on the establishment.

This is not unusual as we often see the outsider narrative used by even the most insider of politicians.

The normal course of events is for a politician to win on sedition, but govern as the establishment.

And then as the political cycle works its magic, and they are in turn ejected by the next outsider railing against the awful incumbents.

Winning politicians are expected to defend their officials and prize values of expertise and truthfulness as part of the job, even if this turns them into an establishment figure, and therefore target, over time.

The news story above [with my red arrows] shows us how far away we are from the normal process with an incumbent who continues to occupy the seditious seat.

We see three elements here of 1) support for the incumbent, 2) attacks on a key official in his government, and 3) promotion of misinformation.

In normal times, we would expect to see the opposition calling for government officials to be fired, and expressing their sedition in conspiracy theories directed at the establishment.

Yet here we see these tactics linked with support for the same President who is, as a matter of fact, responsible for the official’s hiring and for the national policy on vaccination.

This dynamic where an incumbent is able to both wield the power of their office and co-opt the power of seditious opposition is extraordinary.

For those who oppose this President, there is an attraction, if you cannot take his office away, to looking at how you might limit his ability to tap into the power of misinformation as seditious speech.

This has created an unusual interest in controlling political speech that can feel closer to positions held in other countries than to the very hands-off approach we are used to in the US.

It seems unlikely, given the structure of US politics, that this interest will lead to actual regulation but it is a new factor in the cultural climate of the US and this will impact on platforms as well as politicians.

NEXT UP

As I do the thinking that leads up to writing these posts I am finding that ‘one thing leads to another’.

This is the last of a set of three where I wanted to talk about political partisanship and misinformation.

It has prompted me to revisit some thinking about the often discussed question of whether social media platforms should be treated as media publishers and I will move onto this next.

Summary :- I describe some of the ways that governments are using regulation to control political speech including misinformation. I frame this as being within a broader context of attitudes to sedition and talk about the exceptional situation in the US.