We cannot have networked services without there being physical infrastructure carrying signals between the different nodes. At its most basic this infrastructure consists of routes and routers.

The routes are the channels that can carry signals between nodes, either over some kind of cable strung between the nodes or by using wireless spectrum. Nodes must have the right kind of sending and receiving equipment for the relevant technology being used to carry the signals. And they must have a routing capability for the protocols being used so that they can direct signals along the right paths to reach their intended destination.

Unregulated Networks

The internet was developed to provide a ‘network of networks’. And in most cases, it remains possible to construct a local collections of routes and routers to connect devices without seeking permission from any government. These typically use local area network cabling (most commonly today a type called ‘Cat 6’) and/or unlicensed spectrum (generally the 2.4GHz and 5GHz bands).

These unregulated local networks can grow to a significant scale, for example encompassing thousands of devices in a large corporation, but they usually exist within a single entity.

When you want to connect outside of your own managed entity – whether a single home or large organisation – this will normally mean using a commercial network provider for onward access. Once you interconnect your local network you are not free to do just what you want but must work with internet protocols and infrastructure in the Logical layer. It is also means a move into what is a highly regulated space.

Public Networks

Under UK and EU law, the fact of making a network available to the public, as opposed to serving a private set of known users, can trigger a range of regulatory obligations as you are then deemed to be a ‘Public Electronic Communications Network’. Strictly speaking a set of regulatory obligations can apply even if you are just offering public WiFi access in your premises. In practice, many people will not even be aware of these obligations unless something happens that leads to an investigation.

The regulations governing public networks reflect both concerns about there being a scarcity of supply and broader societal interests.

On the scarcity side, this can vary widely between countries but in the UK there have been two broad assumptions.

For wired networks, it was assumed that there was not a commercial case for more than one entity to run a physical cable into all premises in the UK. This is due to the high cost of running new cables down streets given the specific topology and legacy network issues in the UK.

There are some competing UK wired networks especially in dense urban areas but the network originally built by the General Post Office, a department of the government, and transferred to British Telecom (BT) in the 1980’s, remains the only option in many places. The cost of doing this in other countries will be very different so creating climates where it is more or less likely that the market will deliver multiple wired access routes into each property.

For wireless networks, there may also be concerns about the economics of building multiple networks but this is a more attractive proposition as you don’t need to carry out expensive civil works to reach each customer. There is still a need to lay cables to connect cell towers but each cell tower can serve many subscribers. Even if the costs mean that many more entities could afford to build wireless networks than wired ones, the laws of physics provide an additional constraint.

While it would be technically feasible to run hundreds of different cables into a premises if the economics made this desirable, you cannot have hundreds of networks using the same spectrum to reach customers as there is a limit to the amount of data each set of wavelengths can carry.

A fundamental decision for the regulation of the physical routes is whether to allow their owners to operate them exclusively or whether to require owners of routes to open them up to others on government-specified terms.

In the UK the owner of the legacy wired infrastructure has been required to offer access to other providers on the same terms as it has access to sell its own retail network services. Other countries have come up with different solutions. Some believe it is best to encourage the installation of multiple wired networks by continuing to allow exclusive access, while others mandate that some operators provide access to third parties.

Routers

When we consider the routers, the rules here are set more by industry than by governments. At least that has been the case to date. Operators can install any router that meets the technical requirements by complying with industry-developed standards. These standards are an alphabet soup of acronyms, for example DOCSIS for cable networks, ADSL for plain old-fashioned telephony networks, LTE Advanced for mobile etc.

Governments have a role to play in the international bodies that agree on standards but the work is largely technical not political. There are strong incentives to continue to use global standards but if battles over market positions become politicised then it is possible that regions will break away and use local standards.

The markets for routing devices have largely been considered competitive. This may be most apparent in the home networking space where routers can come from many sources. There are major providers of commercial networking equipment that have held strong positions at various times, like Cisco, but other vendors do compete and there are increasingly options to use commodity hardware bypassing major vendors altogether. There is new interest in who builds routers and how they are built today amid concerns over the position of Huawei in 5G mobile equipment.

Patenting and licensing are also areas where regulation and the courts have a significant role to play in the development of network equipment. Manufacturers may use a mix of open and proprietary technology and can get drawn into legal disputes over whether they have the right licenses that impact on what technology can be deployed where.

Information Society Services and Access Market Regulation

A provider of networked services does not necessarily take a view on the specific model for the economic regulation of access networks. Their interest is that as many people as possible should have high quality affordable connections.

If a state monopoly model can deliver internet access more broadly and cheaply than an open competitive model in a particular country then the self-interest of information society services would lie in supporting this. However, there has been a general assumption that regulatory structures which promote competition will deliver more capacity and keep prices lower for the consumer. Competition between access providers is not an end in itself for information society services but a means to an end – fast, cheap broadband for as many people as possible.

The areas of concern for information society services relate to whether access providers will create impediments to them in reaching their users.

At the extreme, the greatest impediment is a complete lack of connectivity. If access providers have no physical route to someone then they have not completed their job as far as the information society service is concerned. So the rollout of broadband is a critical area of interest. Some access providers argue that regulation, especially when this requires open access to their infrastructure, can dampen investment and thereby slow rollout.

If access providers have put a physical route in place but it is not technically capable of meeting the information society service’s needs then this is the next area of concern. Each shift in the technology used to distribute content may require a corresponding upgrade of access networks and this does not necessarily happen in step with demand or evenly across countries.

The major shift to video streaming that is still ongoing as I write has driven the change to what we call ‘high speed broadband’ both in wired and wireless networks. This has been made possible by upgrading the routers in street cabinets and on mobile masts and adding additional capacity along routes from exchanges to the cabinets and masts.

There is a keen interest from information society services in this upgrade happening and they look to governments to push this along where the market is not delivering. Some information society services have also become involved in the provision of access networks either directly as a service provider or by developing technology for third parties to deploy.

Net Neutrality

If the physical conditions of there being an appropriately capable physical link to the user are in place then all should be fine. But there are concerns that economic considerations could come into play here and this is what has motivated the call for additional regulation to be placed on access providers under the banner of ‘net neutrality’,

The core concern is that an owner of a physical link might vary how it routes traffic over the link for commercial or other non-technical reasons. The variation could be to prohibit traffic from a particular node altogether (blocking), to permit the traffic but give it lower priority than default routing would provide (throttling), or to permit the traffic and ask for a fee to give it higher priority in such a way that other traffic will be affected negatively (boosting).

An example of blocking is the way that access providers in a number of countries in the Middle East routinely block VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) traffic. Various motives are claimed for these blocks and access providers and regulators may each point to the other as responsible, but the net effect is to direct people back to the access provider’s own telephony offers. There have been fears about VoIP blocking in other regions but these have not become widespread as access providers shifted their business model away from depending on metred voice revenue. If people are willing to pay for packages with data and unlimited voice calls then there is no direct loss of revenue if they move some or all of their calls to a third party VoIP service.

Concerns over throttling and boosting have largely surfaced with the shift to video. Increasing use of video can overwhelm the capacity of some access networks. Where this happens access providers may want to use throttling to reduce the traffic from particular high bandwidth services. Some network management is reasonable and in the consumer interest but there can be different views on whether particular technical configurations represent simple network management (good) or throttling (bad). Under net neutrality rules, a regulator would have to determine whether or not an access provider was being reasonable when imposing restrictions on traffic.

It may also be tempting for network operators to try to offer an enhanced service to some services for a fee. This offer to ‘boost’ a service may again seem reasonable – if the service is willing to pay and the consumer gets a more reliable service then why not allow this? But the nature of the internet protocols means that prioritising traffic from one service may have the technical effect of slowing down traffic from other services. This may not be an issue where there is plenty of capacity for everyone in the network infrastructure but where that is the case then there is equally no reason for anyone to want to pay for boosting.

Most of the concerns relate to technical impacts but some people are also concerned about economic impacts on the market if differential pricing to end consumer is permitted. In these models, traffic from particular services is typically ‘zero rated’ meaning that the user does not pay for this data while they do pay for data used with other services. There is no technical difference between how the routers handle the traffic of all services but the fact that using some services does not rack up data costs may affect consumer behaviour.

The group of EU telecoms regulators, BEREC, has published guidance on how the EU’s rules on net neutrality are intended to operate that usefully elaborates on all these concerns. The language in the underpinning regulation is also worth looking at as it frames net neutrality in terms of a user ‘right’ to both receive and distribute information and then follows this up with a series of restrictions on internet service providers that are deemed necessary to protect this right :-

Article 3 – Safeguarding of open internet access

End-users shall have the right to access and distribute information and content, use and provide applications and services, and use terminal equipment of their choice, irrespective of the end-user’s or provider’s location or the location, origin or destination of the information, content, application or service, via their internet access service.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32015R2120&from=EN

Security and Privacy Regulation

As well as economic regulation, there may be other societal obligations reflected in the regulation of access providers..

A very common requirement is for access providers to have to offer a ‘lawful intercept capability’, ie they must be able to allow law enforcement agencies to ‘listen in’ to connections over their networks. There are varying degrees of safeguards and public acceptance but the practice is likely to be happening everywhere.

Note that the obligation will generally fall on the licensed network operator. It is not the responsibility of the equipment vendor to provide interception directly. It is rather the case that network operators will ask their equipment vendors for technical solutions to help the service provider meet its legal obligations.

In simple terms, when selling equipment to a UK network operator like BT, equipment vendors may put a ‘backdoor’ in so that traffic can be intercepted. But this will be as a response to the technical specification that BT has set as it meets its obligation to maintain a capability under UK law. Equipment vendors will build a different capability into the equipment sells to network operators in other countries.

This applies consistently for all vendors and in all markets where the network operator is legally required to do this. It is valid to ask whether equipment vendors are leaving other backdoors open that the purchaser did not specify but we should recognise that the original sin of providing a backdoor at all is one that the purchaser has to insist on because of the law they are subject to irrespective of the nationality of the vendor.

Lawful intercept regulation may be tempered with privacy obligations for access network providers. Governments will both order operators to offer up data when legally obligated and require them to keep it secure in all other scenarios.

We see a good example of this is article 5.1 of the EU’s ‘ePrivacy Directive’ (technically the ‘Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive 2009’). This sets out a general confidentiality provision in Article 5 but then creates a set of exceptions in Article 15 that allow for lawful intercept :-

Article 5 – Confidentiality of the communications

1. Member States shall ensure the confidentiality of communications and the related traffic data by means of a public communications network and publicly available electronic communications services, through national legislation. In particular, they shall prohibit listening, tapping, storage or other kinds of interception or surveillance of communications and the related traffic data by persons other than users, without the consent of the users concerned, except when legally authorised to do so in accordance with Article 15(1). This paragraph shall not prevent technical storage which is necessary for the conveyance of a communication without prejudice to the principle of confidentiality.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32002L0058&from=EN

Other Obligations

Regulators of access network operators may also impose obligations on them related to service quality. For example, the UK regulator Ofcom has developed a code of practice that give consumers specific rights if their broadband provider does not deliver promised speeds.

Core Infrastructure

I have described a lot of regulation that governs what is known as the ‘last mile’ connection, ie where a consumer connects with the network. We should not forget the huge amount of infrastructure that connects all these consumer networks with each other and with the data centres where software services live.

This core infrastructure is not regulated in the same way as access networks. It is provided by a mix of different institution types. There are many straightforward commercial arrangements, for example services have to buy capacity to get data into and out of their data centres. The providers of that capacity will have to comply with regulation but the deals will usually be at commercial rather than regulated rates.

The prices consumers pay for internet services will reflect all of these core network costs. For information society services, the costs of getting their data onto the network will be factored into the subscriptions they charge or the amount of advertising they show. For internet access providers, the costs of connecting with other networks will be recovered through user data charges.

A common claim from internet access providers is that information society services are getting a ‘free ride’ because they do not pay for the access providers’ costs. The apportionment of costs for delivering internet services is worth further study and discussion but current structures are now quite mature and rational and do involve considerable investment in network infrastructure by information society services.

One of the ways that all parties have sought to manage costs is through the development of internet exchange points (IXPs). These allow for more efficient, and therefore cheaper, routing of data in the core network. There are many different models for doing this from the purely commercial through to public sector ownership. These exchanges may require regulatory approval or be outside formal regulation depending on local law.

Information Society Services and Net Neutrality

Providers of internet services tend to be cautious about regulation. Yet they are generally full-throated supporters of legally-enforced net neutrality. Some access network providers have criticised this as evidence of double standards. And there have been calls for ‘neutrality’ requirements to be imposed at these higher Data, Content and Commerce layers.

I will explore concerns about neutrality at the higher layers later but would note here that blocking at the Physical layer is different from anything information society services may do further up the stack. If an access provider puts a technical block in place then there is no way for consumers to access that service.

If a service is de-listed by a search engine or banned from an intermediary platform then this can certainly have a massive impact on their discoverability but this is not an absolute block. They can still reach their customers directly and try to find alternative ways to promote themselves.

Indeed, the rationale for the UK authorities ordering access network blocks of services like PirateBay is a recognition that this is the most robust way to restrict access versus requiring search engines or intermediaries to delist them.

Future Regulation

Could physical networks ever be unregulated? This is hard to imagine as long as governments decide what happens with spectrum and public streets and as long as networks need to route across licensed spectrum and along highways.

People have stretched unlicensed spectrum far more than might have been expected. You could imagine a world where cells using unlicensed wireless spectrum become so capable using mesh technology that many routes do not depend on regulated access providers. But if this does materialise it is as likely that governments would try to push licensing requirements down onto micro providers as it is for them to give up on regulating physical networks altogether.

We might see this play out in a similar way to the debate about traditional media and social media. As people have shifted attention away from traditional media that is subject to specific sectoral regulation to social media which is not, the pressure to regulate the new forms of media has grown steadily.

As people move from regulated to unregulated networks then similar pressures would apply. We already see in areas like the shift from SMS, offered by regulated telecoms services, to new internet-based messaging services. I will expand on this as I move on to discuss the Functional layer.

Example 4 – Offering a Video Streaming Service

It is important to recognise what the regulation of the physical layer does and does not do. It does not mean that all internet services will be experienced in exactly the same way by end users but it does provide a baseline level of connectivity. And regulation does not determine all the costs paid by each party in a transaction, which are mostly based on commercial arrangements, but may be a key factor in consumer broadband pricing.

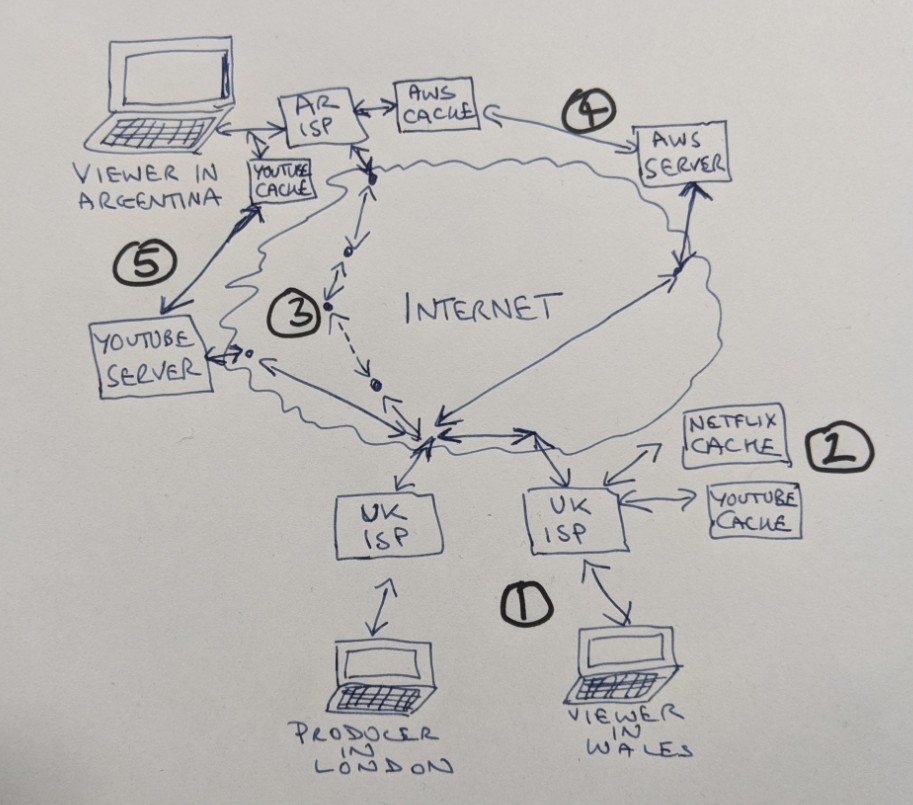

Let’s imagine I have produced a series of Welsh language exercise videos from my home in London. The series is called “Gadewch I Ni Fynd Yn Gorfforol”. For someone to consume the video content I produce it has to be able to get from my server to their end device, typically a phone, computer or smart TV.

I set up some video serving software at home and offer the videos to the world. I gain a few dedicated viewers in Wales and their experience is mostly good as my internet access provider has good connections with their providers (in many cases it is the same company). It is a few short hops over fast connections between my server and the homes of my audience (1).

Under EU/UK net neutrality rules, my data is treated equally with the data of major providers like Netflix and YouTube when a viewer requests my videos. While they also have UK caching servers (2) this does not give them a significant advantage over my good local connection. When viewers do have problems it is because they are in rural areas where local connections are slow. But this affects all video services equally – when they watch YouTube and Netflix they get the same jitters so my videos are no worse than anyone else’s.

The costs of sending the video are shared between me and the viewer as we each pay our access providers a monthly fee that covers the cost of connecting our homes and of our traffic flows to and from the wider internet. And ISPs will not ask me to pay extra to prioritise my video traffic over this ‘last mile’ connection to the user as this is prohibited in regulation.

But as I gain more viewers they tell me their experience is suffering as my domestic connection with an upload speed of only 10 Mbps has become a bottleneck. Luckily, I live in a part of London where providers are offering new fast fibre connections. I can install this and can now serve lots more users based on the same cost sharing model. I pay more each month but this is still a simple fee to cover my side of each connection – we have just increased the volume of simultaneous connections.

Word of my videos spreads and they start to become popular in Patagonia where there is a Welsh-speaking community in southern Argentina. But these viewers find that their experience is poor as their connections to my server in London depend on a series of varying quality links between their access provider and mine. My upgraded connection into the UK network means I have capacity to serve them all but each individual experience can be slow because of what happens when the data leaves my local provider’s network. There are multiple hops between me and these new more distant users and they do not all run at the speed I am used to with my domestic UK viewers (3).

If I want these viewers to have a good experience I need to serve my videos from somewhere with better connectivity to them than my London home. There are two common ways for me to do this.

One is to move my video service to a cloud provider like Amazon Web Services (AWS). AWS has infrastructure in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where a local copy of my videos can be served up to local users (4). AWS have commercial agreements with Argentinian ISPs for this local access and my fees to AWS pay a proportion of the costs for these.

For my Patagonian users we have a new cost sharing model. I can pay less to my UK access provider than for my viewers in Wales as I now use my local connection to upload videos once to AWS but not to serve each individual user. I have a new cost as I have to pay AWS to cover a share of their data centre, local caching infrastructure and global connectivity costs. And the local viewer pays their Argentinian ISP for the last mile connection.

As an alternative to global cloud providers I could instead pay a local Argentinian company to host and serve my content. Before the arrival of the global cloud services, this would have been the default way to expand into a new market. I am more likely to choose a global cloud provider today because of the convenience of technical and financial administration, especially if I plan to expand into multiple markets, rather than because they are necessarily offering faster or cheaper data transfers to my viewers.

The other way I can go is to move my videos to a platform like YouTube. I again reduce my local access costs as I just need to upload videos and not serve them on an ongoing basis. YouTube uses Google’s caching infrastructure which includes servers in Buenos Aires so my videos work well. In fact they even have an edge node in Rio Gallegos in Patagonia so they are really close to my viewers (5).

The cost sharing model for this kind of video serving now moves much of the cost to YouTube. I can use a cheap basic domestic connection for the one time upload of my videos to YouTube’s servers and my viewers only pay for their standard local access services. YouTube pays for the data centres, local caching infrastructure and global connectivity and, in return, they claim a majority share of any revenue that is generated by advertising alongside my content.

This is the simplest model for me to administer technically and financially but gives me the least control over the Data and Commerce layers in my model. For the most part, I cannot control the collection and use of data of my viewers and I am bound in to YouTube’s methods for the monetisation of content. There may also be issues in the Content layer as YouTube set the rules for what are acceptable videos on their platform.

Regulation govern the last mile and first mile connections which feature in all these models in quite some detail and this may include regulated pricing as well as net neutrality provisions. For the rest of the data transmission there will usually be a need for government permits where new infrastructure is being built and there may be licensing requirements for a broad range of telecoms infrastructure including exchanges and caching servers.

But the data flows are also heavily dependent on commercial agreements between the connecting parties rather than being regulated end-to-end. This means there is no single consistent experience of my video content ‘over the internet’. There are rather many different options for me to decide between in order to deliver my content to people in different places and these each have their pros and cons.

Summary :- the physical infrastructure that supports networked services is highly regulated. It uses technical standards which are set by a variety of non-governmental bodies. But the deployment of equipment and offering of access services at scale usually depends on securing licenses from governments. The conditions attached to those licenses are core to what it means to regulate Physical layer. There has been particular interest in the concept of ‘net neutrality’ in the internet community.